In my last post, I waxed theoretical. I discussed the potential reasons for measuring serial hemoglobin or hematocrit levels, the limitations due to the rate of change of the values, and conjectured about how often they really should be drawn.

And now, how about something more practical? How about an some actual research? One of the more common situations for ordering serial hemoglobin draws occurs in managing solid organ injury. The vast majority of the practice guidelines I’ve seen call for repeating blood draws about every six hours. The trauma group at the University of Florida in Jacksonville decided to review their experience in patients with liver and spleen injuries. Their hypothesis was that hemodynamic changes would more likely change management than would lab value changes.

They performed a retrospective review of their experience with these patients over a one year period. Patients with higher grade solid organ injury (Grades III, IV, V), either isolated or in combination with other trauma, were included. Patients on anticoagulants or anti-platelet agents, as well as those who were hemodynamically unstable and were immediately operated on, were excluded.

Here are the factoids:

- A total of 138 patients were included, and were separated into a group who required an urgent or unplanned intervention (35), and a group who did not (103)

- The intervention group had a higher ISS (27 vs 22), and their solid organ injury was about 1.5 grades higher

- Initial Hgb levels were the same for the two groups (13 for intervention group vs 12)

- The number of blood draws was the same for the two groups (10 vs 9), as was the mean decrease in Hgb (3.7 vs 3.5 gm/dl)

- Only the grade of spleen laceration predicted the need for an urgent procedure, not the decrease in Hgb

Bottom line: This is an elegant little study that examined the utility of serial hemoglobin draws on determining more aggressive interventions in solid organ injury patients. First, recognize that this is a single-institution, retrospective study. This just makes it a bit harder to get good results. But the authors took the time to do a power analysis, to ensure enough patients were enrolled so they could detect a 20% difference in their outcomes (intervention vs no intervention).

Basically, they found that everyone’s Hgb started out about the same and drifted downwards to the same degree. But the group that required intervention was defined by the severity of the solid organ injury, not by any change in Hgb.

I’ve been preaching this concept for more than 20 years. I remember hovering over a patient with a high-grade spleen injury in whom I had just sent off the requisite q6 hour Hgb as he became hemodynamically unstable. Once I finished the laparotomy, I had a chance to pull up that result: 11gm/dl!

Humans bleed whole blood. It takes a finite amount of time to pull fluid out of the interstitium to “refill the tank” and dilute out the Hgb value. For this reason, hemodynamics will always trump hemoglobin levels for making decisions regarding further intervention. So why get them?

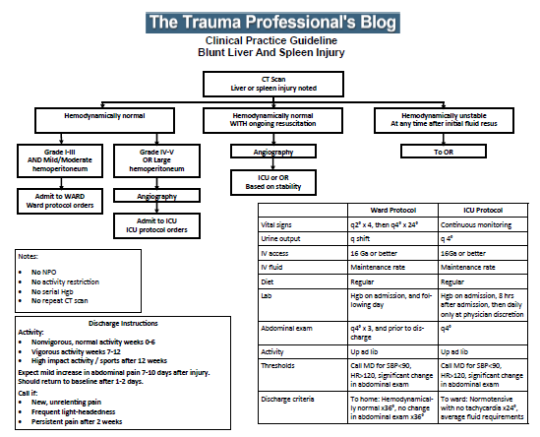

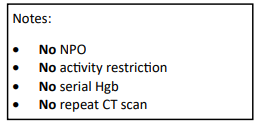

Have a look at the Regions Hospital solid organ injury protocol using the link below. It has not included serial hemoglobin levels for 18 years, which was when it was written. Take care to look at the little NO box on the left side of the page.

I’d love to hear from any of you who have also abandoned this little remnant of the past. Unfortunately, I think you are in the minority!

Click here for the Regions Hospital Solid Organ Injury Protocol

Reference: Serial hemoglobin monitoring in adult patients with blunt solid organ injury: less is more. J Trauma Acute Care Open 5:3000446, 2020.