How many times has this happened to you? You walk into a young, healthy trauma patient’s room and discover that they have nasal prongs and oxygen in place. Or better yet, these items appear overnight on a patient who never needed them previously. And the reason? The pulse oximeter reading had been “low” at some point.

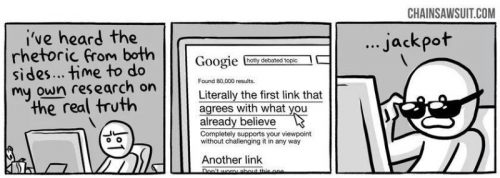

This phenomenon of treating numbers without forethought has been one of my pet peeves for years. Somehow, it is assumed that an oximetry value less than the standard “normal” requires therapy. This is not the case.

In young, healthy people the peripheral oxygen saturation values (O2 sat) are typically 96-100% on room air. As we age, the normal values slowly decline. If we abuse ourselves (smoking, working in toxic environments, etc), lung damage occurs and the values can be significantly lower. Patients with obstructive sleep apnea will have much lower numbers intermittently through the night.

So when does a trauma inpatient actually need supplemental oxygen? Unfortunately, the literature provides little guidance on what “normal” really is in older or less healthy patients. Probably because there is no norm. The key is that the patient must need oxygen therapy.

But how can you tell? Examine them! Talk to them! If the only abnormal finding is patient annoyance due to the persistent beeping of the machine, they don’t need oxygen. If they feel anxious, short of breath, or have new onset tachycardia, they probably do. Saturations in the low 90s or even upper 80s can be normal for the elderly and smokers.

Bottom line: Don’t get into the habit of treating numbers without thinking about them. There are lots of reasons for the oximeter to read artificially low. There are also many reasons for patients to have a low O2 sat reading which is not physiologically significant. So listen, talk, touch and observe. Set the alarm level to 90%, or even lower. And if your patient is comfortable and has no idea that their O2 sat is low, turn off the oxygen and toss the oximeter out the window.