My series on the massive transfusion protocol (MTP) continues! Today, I’ll provide some tips on the logistics of your MTP.

MTP logistics include details such as who will be delivering the blood, what actually goes in each cooler, what ratios should be used, limitations imposed by the use of frozen plasma, and documentation. I’ll discuss details about ratios and FFP in the next Trauma MedEd newsletter.

The runners who travel between the blood bank and the patient need to be selected carefully. Blood bank tech? Not ideal because they’ve got more important work to do. ED or OR tech? Maybe, as long as you’ve got a reliable pool. Student or resident? Probably not, because they may not know their way to the blood bank, which is typically placed in the farthest corner of the basement as possible. One of the most creative solutions I’ve seen is the use of a hospital security officer. Think about it. They know the hospital layout cold, including that obscure corner where the blood bank is located. And there are plenty around all the time!

Documentation is critically important, both in the trauma bay and the blood bank. Trauma activations, especially ones requiring MTP, are very fast-moving and complex. Two sets of documentation are crucial: accurate records of blood product administration (on the trauma flow sheet), and documentation of just about everything else (in the blood bank). A specific timestamp on the trauma flow sheet that records the exact time of activation of MTP is a big plus.

What about coolers? I’ve seen everything used from uninsulated plastic buckets, picnic coolers, and pneumatic tube containers to large, self-contained rolling refrigeration units. The choice of container really boils down to cost vs waste. The cheaper the container is, the less insulated it is, the more likely that blood products will be discarded due to high temperature if not transfused promptly. The best blend of cost vs utility seems to be the good, old-fashioned picnic cooler. It’s very portable, reasonably cheap, and can be tested for temperature maintenance. Just be sure to secure a pouch to the outside to keep platelets at room temperature to maintain full functionality.

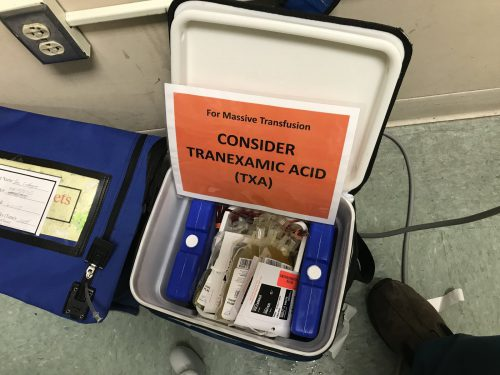

Here’s a sample MTP cooler that’s ready for use. The platelets are in the pouch on the left. Note the reminder to prompt the team to give TXA if not contraindicated. This is often forgotten in the heat of the trauma activation.

Who actually runs your MTP? In some ways, it should run itself. Coolers get delivered, products get transfused. However, some decision making is needed to decide how long to continue and whether any tweaking of product ratios needs to happen. In the emergency department, the surgeon or emergency physician can do this. But once a trauma patient arrives in the OR, that is no longer the case. The emergency physician was left behind in the ED and the surgeon is up to her elbows in trouble. What about the anesthesiologist? Nope, they are busy keeping the patient safely asleep, regulating rapid infusions, and actually administering the blood.

Most of the time, however, these two physicians actually end up running the MTP while multi-tasking at their other job. Unfortunately, this can lead to errors and delays. One best practice to consider: a highly trained trauma resuscitation nurse or advanced practice provider (APP) can run the MTP from the sidelines. They travel with the patient from ED to OR, managing the MTP the entire time. This offloads responsibility from busier people.

In the next post, I’ll continue with MTP deactivation and analysis.