Adult trauma patients are at risk for venous thromboembolism (VTE). Children seem not to be. The big question is, when do children become adults? Or, at what age do we need to think about screening and providing prophylaxis to kids? As of yet, there are no national guidelines for dealing with DVT in children.

Researchers at Johns Hopkins went to the NTDB to try to answer this question. They looked at the records of over 400,000 trauma patients aged 21 or less who were admitted to the hospital.

Here are the interesting factoids:

- Only 1,655 patients (0.4%) had VTE (1,249 DVT, 332 PE, 74 DVT+PE)

- VTE patients were older, male, and frequently obese

- VTE patients were more severely injured, with higher ISS and lower GCS

- Patients with VTE were more likely to be intubated and receive blood transfusions, and had longer hospital and ICU stays

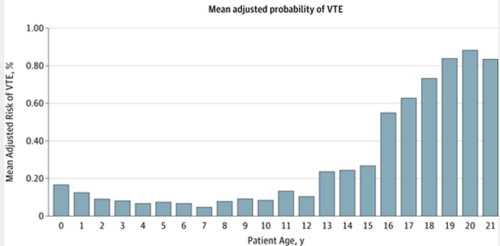

The risk of VTE stratified by age was as follows:

Bottom line: Risk of VTE in pediatric trauma patients follows the usual injury severity pattern. But it also demonstrates a predictable age distribution. Risk increases as the teen years begin (13), and rapidly becomes adult-like at age 16. Begin your standard surveillance practices on all 16 year olds, and consider it in 13+ year olds if their injury severity warrants.

Related post:

Reference: Venous thromboembolism after trauma: when do children become adults. JAMA Surgery online first October 31, 2013.