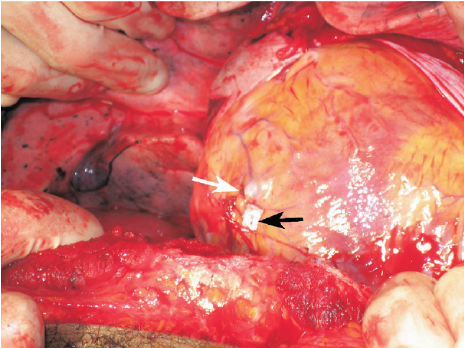

I previously described a young man who was recovering from surgery for repair of a stab to the heart. He presented shortly after discharge with fever, a slightly elevated WBC, some EKG changes, and a small pericardial effusion.

Several people tweeted out the answer, which is post-pericardiotomy syndrome (PPS).

PPS is an inflammatory reaction to traumatic and then surgical injury to the pericardium. It is seen in a relatively small percentage of patients who undergo pericardiotomy for trauma, which is why patients who develop it are such a surprise to trauma professionals. A similar condition can develop after myocardial infarction (Dressler syndrome) and was first described in 1956. The classic paper describing PPS after trauma was published five years later (cited below).

Symptoms typically develop 1-6 weeks after surgery, and usually consist of low grade fevers, malaise, chest pain, and occasionally arthralgia. A pericardial friction rub may be present (and where is that stethoscope, BTW?). The WBC is usually elevated, with some degree of left shift. EKG may show some degree of pericarditis, including global ST elevation and T wave inversion.

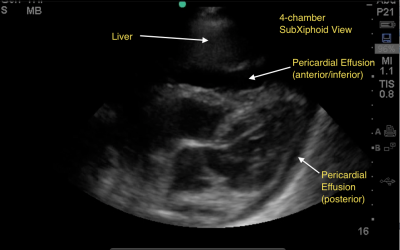

Chest x-ray is usually nonspecific, but may show pleural effusion or an enlarged heart due to the presence of some pericardial fluid. Ultrasound may confirm a pericardial effusion, but this is not a reliable finding since the pericardium is typically left open at the end of the operation.

Treatment is symptomatic, usually consisting of NSAIDS or aspirin to tone down the inflammatory response. These drugs are usually given for 4-6 weeks, then tapered. If the effusion is large, pericardiocentesis may be needed.

Bottom line: If your postop heart injury patient presents with these symptoms, consider infectious etiologies first, but remember that they are typically even less common than post-pericardiotomy syndrome. Reassure your patient, then reach for the ibuprofen to get them through it.

Reference: Postpericardiotomy syndrome following traumatic hemopericardium. Am J Cardiology 7(1):83-96, 1961.