There are a lot of opinions and not so much literature on how to manage chest tube air leaks. Here is some practical advice on how to deal with this occasional problem.

Most air leaks are an alveolar-pleural fistula, representing a connection between a very small airspace and the pleura. This should not be confused with a bronchopleural fistula, which involves larger airways and is much more challenging to manage.

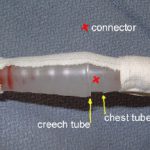

First, identify what kind of leak it is. Remember, dry seal chest tube systems will not show an air leak unless it has a fluid chamber that can be filled with water (see related post below).

- Expiratory – occurs during normal expiration only

- Forced expiratory – occurs only with coughing

- Inspiratory – occurs during inspiration in ventilated patients

- Continuous

Inspiratory leaks are rare and should be managed conservatively with maneuvers to minimize airway pressures. Continuous air leaks can be monitored, but may indicate a bronchopleural fistula.

Expiratory and forced expiratory types account for about 98% of all air leaks. Small air leaks should be managed with water seal, not with increased suction. The main concept is to reduce air flow through the fistula so it can heal. A prospective study has shown that this technique stops small to moderate size leaks sooner than leaving on suction.

Larger air leaks will probably not seal on their own and are probably not safe to place on water seal. They will likely require pleurodesis, either chemical or mechanical via a VATS procedure. Blood and fibrin patches have also been tried.

Any air leak that extends hospital stay should be evaluated for appropriateness of discharge with a Heimlich valve or VATS pleurodesis.

References:

- A prospective algorithm for the management of air leaks after pulmonary resection. Ann Thoracic Surg 66:1726-1731, 1998.

- Prospective randomized trial compares suction versus water seal for air leaks. Ann Thoracic Surg 71:1613-1617, 2001.

Related posts: