The annual meeting of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) begins in two weeks. Today, I will kick off a series of commentaries on many of the abstracts being presented at the meeting. All readers should be aware that I have only the abstracts to work with. As I always caution, final judgement cannot be passed until the full paper has been reviewed. And many of these will not make the jump to light speed and ever get published. So take them with a grain of salt. They may point to some promising developments, but then, maybe not.

First up is a nice analysis on the price of being a trauma center. One of my mentors, Bill Schwab, always used to say that trauma centers are always in a state of “high-tech waiting.” It costs money to keep surgeons in house, other medical and surgical specialists at the ready, and an array of services and equipment available at all hours. Any hospital administrator can tell you that trauma is expensive. But how expensive, exactly?

The trauma group at the Medical Center of Central Georgia in Macon did a detailed analysis of the cost of readiness for trauma centers in the year 2016. The Georgia State Trauma Commission, trauma medical directors, trauma program managers, and financial officers from the Level I and II centers in Georgia determined the various categories and reported their actual costs for each. An independent auditor reviewed the data to ensure reporting consistency. Significant variances were analyzed to ensure accurate information.

Here are the factoids:

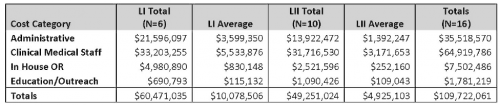

- Costs were lumped into four major categories: administrative, clinical medical staff, in-house OR, and education/outreach

- Clinical medical staff was the most expensive component, representing 55% of costs at Level I centers and 65% at Level II

- Only about $110,000 was spent annually on outreach and education at both Level I and II centers, representing a relative lack of resources for this component.

- Total cost of being a Level I center is about $10 million per year, and $5 million per year for Level II

Here is a copy of the table with the detailed breakdown of each component:

Bottom line: Yes, it’s expensive to be a trauma center. It’s a good idea for any trauma center wannabe to perform a detailed analysis to make sure that it makes sense financially. This is most important in areas where there are plenty of trauma centers already. Tools have been developed to determine how many trauma centers will fit within a given geographic area (see below). Unfortunately, very few if any states use this tool to determine how many centers are reasonable. In come cities, it’s almost like the wild west, with centers popping up at random all over the place. This abstract suggests that an additional analysis is mandatory before taking the plunge into this expensive business.

Related post:

Reference: How much green does it take to be orange? Determining cost associated with trauma center readiness. Podium abstract #18, session VIII, AAST 2018.