The management of penetrating injuries to the neck has changed very little over the years. Could it be time? Today, I’ll review some of the basics of classic diagnosis and treatment. In my next post, I’ll discuss an alternative way to approach it.

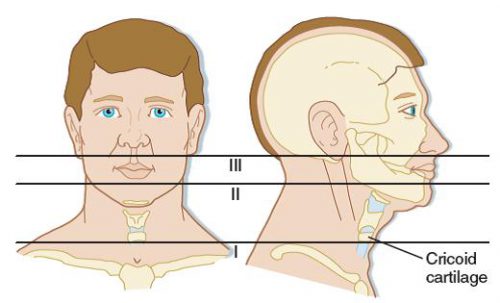

First, lets look at the time-honored zones of the neck. Here’s a nice diagram from EMDocs.net:

The zones are numbered in reverse, from bottom to top, and in Roman numerals.

The area below the cricoid cartilage is considered Zone I and contains many large vascular and aerodigestive structures that are relatively difficult to approach surgically. For this reason, diagnostic testing is recommended to assist in determining if an operation is actually needed and what the best surgical exposure would be. Obviously, this can only be considered in the stable patient. Unstable patients must go straight to the OR and the trauma surgeon will determine the surgical approach on the fly.

Similarly, the area above the angle of the mandible is Zone III, and is also difficult to expose. Injuries to this area may involve the distal carotid and vertebral arteries near the base of the skull, as well as the distal jugular vein. Surgical approach may require dislocation of or fracturing the mandible to get at this area. This is challenging and not that desirable, and few surgeons are familiar with the technique. For this reason, imaging is very desirable and often demonstrates that no significant injury is present. And endovascular / angiographic techniques are now available that may obviate the need for surgery.

Zone II is everything in-between the mandibular angle and cricoid cartilage. This is the surgical Easy Button. Exposure is simple and the operation is fun. In the old days, an injury to this area went straight to the OR regardless of whether there were signs or symptoms of injury. Yes, there were quite a few negative explorations. But we’ve become more selective now with the advent of improved resolution of our CT scans.

Currently, we usually follow a two-step approach to penetrating neck trauma:

- Are there hard signs of injury present? These tell us that a structure that absolutely needs to be fixed has been injured. The patient should be taken directly to OR after control of the airway, if appropriate. Typical hard signs are:

- Airway compromise

- Active air bubbling from wound

- Expanding or pulsatile hematoma

- Active bleeding

- Hematemesis

- What zone is the injury in? And don’t just look at the obvious entry point. Gunshots (and long knives) may enter multiple zones. The zone then determines what happens next:

- Zone I – CT angio of neck and chest. If positive, proceed to OR for repairs, and perform EGD and/or bronchoscopy as needed

- Zone II – Old days: proceed to operating room for exploration, or angiogram, EGD, direct laryngoscopy, and bronchoscopy. Most chief residents chose the former. Current day: CTA of neck, followed by OR, EGD, bronchoscopy only if indicated.

- Zone III – CT angio of the neck. If positive, consider angiography/endovascular consultation vs operation.

Changes from old days to more current thinking have been made possible by improvements in speed and resolution of our CT scanners. But why can’t we take this another step forward and streamline this process even more? I’ll propose some changes in my next post!

Reference: Western Trauma Association Critical Decisions in Trauma:

Penetrating neck trauma. J Trauma 75(6):936-940, 2013.