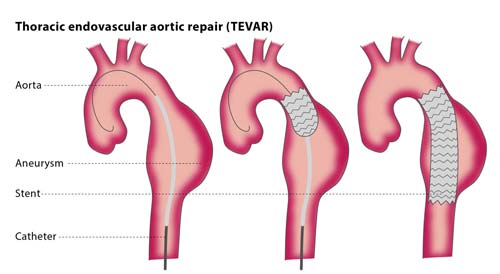

For decades, the treatment of blunt injury to the thoracic aorta was open repair. The big debate at the time was use of cardiac bypass vs fast clamp and sew. But starting in 1997 with the introduction of thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR) of this injury, we have rapidly moved to the point where most traumatic aortic injuries are repaired using this technique.

A report that was written nearly a decade ago indicated a relatively high complication rate for the procedure. Graft complications were reported in 18% of patients, with 14% showing endoleaks. Stroke and left arm ischemia were also reported.

The diagram above shows insertion for management of an aneurysm, but the technique is similar for trauma. Blunt aortic injury occurs closer to the left subclavian artery and care must be taken to place the endograft closer to but not covering its orifice.

As the insertion systems and stents improved, short term events have been on the decline. Unfortunately, long term followup data has been hard to come by.

Until now. An article that is not yet in print reports 11 years of experience and followup with patient undergoing TEVAR at the ShockTrauma center in Baltimore.

Here are the factoids:

- 88 patients underwent TEVAR during the study period, all from blunt trauma

- Average ISS was 38, showing these patients were severely injured

- Overall mortality was 7%, but none was due to the TEVAR procedure

- TEVAR-related complication rate was 9% Endoleaks at the ends of the graft occurred in 4 patients, and all required repair. There were 4 other minor leaks that resolved on their own.

- 26 had all or part of the left subclavian orifice covered at initial operation. None developed ischemia, although 2 had a prophylactic carotid-subclavian bypass before TEVAR.

- The longest followup imaging occurred 8 years after the procedure. No long-term complications were noted.

Bottom line: TEVAR has essentially replaced open repair of the aorta, except in special cases. We continue to learn from our experience, and the complication rate is still falling. Other than endoleaks recognized in the postop period, most other complications rarely occur. Long term followup is poor, but in the patients who do return, there were no complications. But remember, this is an expected sampling bias. If the patient had major problems and/or died, they would just be lost to followup. We would never know.