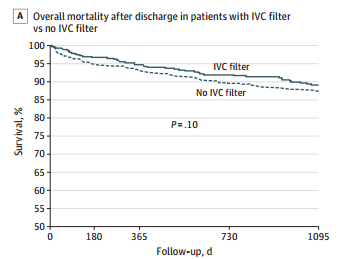

There is a fascinating letter in the New England Journal of Medicine submitted by authors from the Boston Medical Center and Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Like all trauma professionals, they were concerned with droplet contamination produced during the intubation process. Most hospitals have modified their intubation procedures to try to protect personnel as much as possible.

The authors designed a Plexiglas box with two holes for the arms of the intubator that is placed over the patient’s head. This should serve to shield them, and other personnel in the room if the patient unexpectedly coughs during the process. They tested this concept using an intubation mannequin. First, they placed a balloon filled with fluorescent dye in its mouth and slowly inflated until it burst. Here was the result when viewed under ultraviolet light. Sputum everywhere!

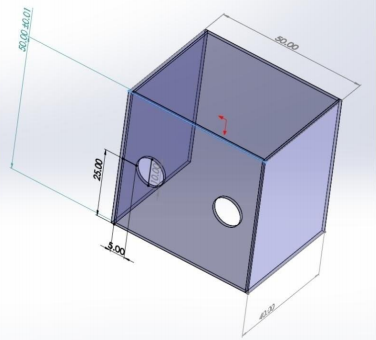

Next, they placed the intubation shield over the patient. Here is a drawing of its dimensions.

The device is open on the bottom and on the side away from the intubator. The arm holes are 10cm in diameter.

The authors then repeated the balloon experiment with the shield in place and the intubator’s arms inserted through the holes. The resulting contamination was limited to their hands and forearms, and the inside of the shield.

Bottom line: This is a very interesting yet simple and cheap device that can be built by just about anyone and should protect personnel from droplet contamination. It will not have much effect on aerosols escaping into the room, but that’s what our other PPE are for! It’s a great example of how creativity is key in keeping us all safer during this pandemic.

You can view the video on the NEJM website at:

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMc2007589

Reference: Barrier Enclosure during Endotracheal Intubation. NEJM DOI: 10.1056/NEJMc2007589, April 4 2020.