I’ve previously written about the difficulties estimating how much blood is on the ground at the trauma scene. In general, EMS providers underestimated blood loss 87% of the time. The experience level of the medic was of no help, and the accuracy actually got worse with larger amounts of blood lost!

A group in Hong Kong developed a color coded chart (nomogram) to assist with estimation of blood loss at the scene. It translated the area of blood on a non-absorbent surface to the volume lost. A convenience study was designed to judge the accuracy that could be achieved using the nomogram. Sixty one providers were selected, and estimated the size of four pools of blood, both before and after a 2 minute training session on the nomogram.

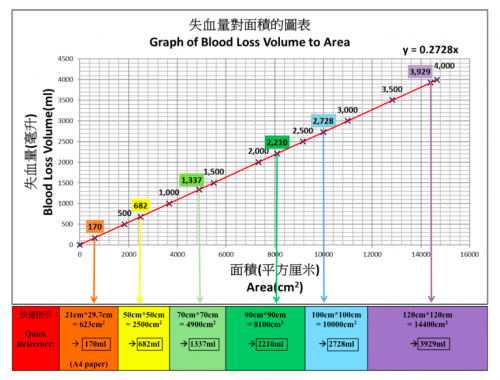

Here’s what it looks like:

Note the areas across the bottom. In addition to colored square areas, the orange block is a quick estimate of the size of a piece of paper (A4 size since they’re in Hong Kong!)

Here are the factoids:

- The 61 subjects had an average of 3 years of experience

- Four scenarios were presented to each: 180ml, 470ml, 940ml, and 1550ml. These did not correspond exactly to any of the color blocks.

- Before nomogram use, underestimation of blood loss increased as the pool of blood was larger, similar to the previous study

- There was a significant increase in accuracy for all 4 scenarios using the nomogram, and underestimation was significantly better for all but the 940ml group

- Median percentage of error was 43% before nomogram training, vs only 23% after. This was highly significant.

Bottom line: This is a really cool idea, and can make estimation of field blood loss more accurate. All the medic needs to do is know the length of their shoe and the width of their hand in cm. They can then estimate the length and width of the pool of blood and refer to the chart . Extrapolation between colors is very simple, just look at the line. The only drawback I can see occurs when the blood is on an irregular or more absorbent surface (grass, inside of a car).

Related posts:

- Can prehospital providers accurately estimate blood loss: part 1

- How soon to extricate the pinned patient?

Reference: Improvement of blood loss volume estimation by paramedics using a pictorial nomogram: a developmental study. Injury article in press Oct 2017.