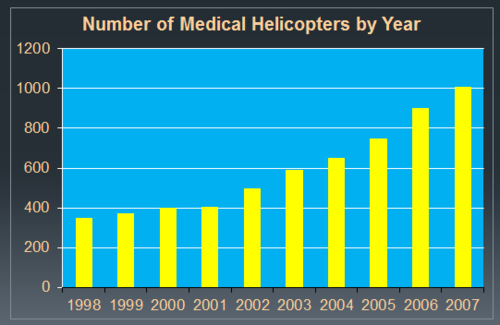

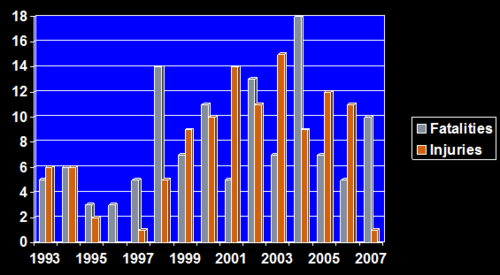

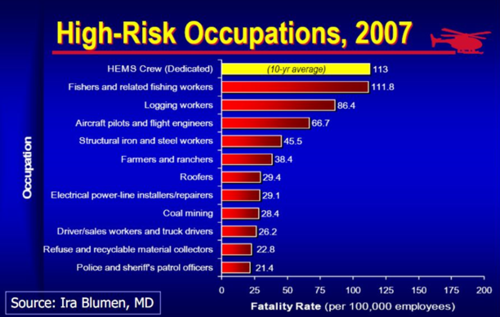

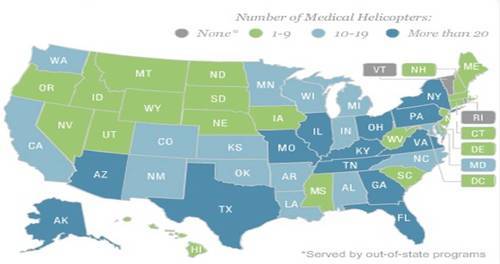

Helicopter transport is an integral and important part of modern day trauma care. Since the inception helicopter emergency medical services (HEMS) for civilian use in the 1970’s, its use has been steadily increasing. And it’s expensive, at least five times more costly than ground transport. Plus, there are risks to both crew and patient, in that there have been 200 deaths of both patients and flight crews. Indeed, flight crews have one of the riskiest jobs, with 5 times more on-the-job deaths than police officers.

So it becomes very important to make sure that this mode of transport is justified. As I wrote previously, the adult HEMS literature is extensive, but not terribly convincing. There is far less data available regarding pediatric patients. And the data that does exist suggests that there may be significant overtriage and overuse.

A study using the National Trauma Data Bank (NTDB) was performed by researchers at Duke University. They reviewed the data for a 5 year period (2007-2011), which is fairly old in my opinion. And they included “children” up through age 18, which are also a bit old, in my opinion. Since there are no real quantitative criteria for overtriage in place, the authors picked three: low injury severity (ISS<10), normal physiology (RTS=12), and low predicted mortality using TRISS (<5%). A total of 127,489 patient records were analyzed.

Here are the factoids:

- 14% arrived via helicopter EMS, 56% by ground EMS, and 29% by private vehicle or walk-in

- HEMS patients were more likely to have head, thoracic, or abdominal injuries, and overall severe injuries (good!)

- Adjusted mortality for patients transported by air was significantly less than for ground (really good)

- 38% of HEMS patients had ISS < 9, and 66% had completely normal physiology (bad)

- Overall, 32% to 82% of children did not meet criteria for appropriate transport

Bottom line: There are a number of flaws in this study that could be improved upon. However, it does provide some interesting data. Helicopter transport does save lives in the younger population, and was estimated at 2 per 100 flights. This is very promising. However, offsetting this was the fact that nearly half of transports failed one or more arbitrary appropriateness criteria. The recommendations I published yesterday need to be adopted, and both state trauma systems and local EMS agencies need to develop and enforce guidelines to optimally use this valuable and expensive resource.

Reference: Current use and outcomes of helicopter transport in pediatric trauma: a review of 18,291 transports. J Ped Surg in press 27 Oct 2016.