Trauma programs use a number of quality indicators and PI filters to evaluate both individual and system performance. The emergent trauma laparotomy (ETL) is the index case for any trauma surgeon and is performed on a regular basis. However, this is one procedure where individual surgeon outcome is rarely benchmarked.

The trauma group in Birmingham AL performed a retrospective review of 242 ETLs performed at their hospital over a 14 month period. They then excluded patients who underwent resuscitative thoracotomy prior to the laparotomy. Rates of use of damage control and mortality at various time points were studied.

Here are the factoids:

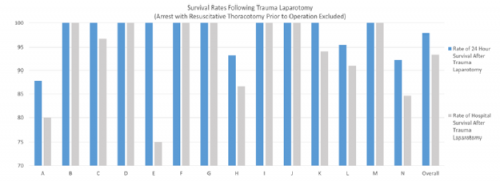

The chart shows the survival rates after ETL at 24 hours (blue) and to discharge (gray) for 14 individual surgeons.

- Six patients died intraoperatively and damage control laparotomy was performed in one third.

- Mortality was 4% at 24 hours and 7% overall

- ISS and time in ED were similar, but operative time varied substantially (40-469 minutes)

- There were significant differences in individual surgeon mortality and use of damage control

The authors concluded that there were significant differences in outcomes by surgeon, and that more granular quality metrics should be developed for quality improvement.

Bottom line: I worry that this work is a superficial treatment of surgeon performance. The use of gross outcomes like death and use of damage control is not very helpful, in my opinion. There are so, so many other variables involved in who is likely to survive or the decision-making to consider the use of damage control. I am concerned that a simplistic retrospective review without most of those variables will lead to false conclusions.

It may be that there is a lot more information here that just couldn’t fit on the abstract page. In that case, the presentation should clear it all up. But I am doubtful.

We have already reached a point in medicine where hospitals with better outcomes for patients with certain conditions can be identified. These centers should be selected preferentially to treat stroke or pancreatic cancer, or whatever there benchmark-proven expertise is. It really is time for this to begin to trickle down to individual providers. A specific surgeon should be encouraged to do what they are demonstrated to be really good at, and other surgeons should handle the things the first surgeon is only average at.

But I don’t think this study can provide the level of benchmarking to suggest changes to a surgeon’s practice or the selection of a specific surgeon for a procedure. A lot more work is needed to identify the pertinent variables needed to develop legitimate benchmarks.

Here are my questions for the presenter and authors:

- Show us the details of all of the variables you analyzed (ISS, NISS, time in ED, etc) and the breakdown by surgeon.

- Are there any other variables that influence the outcome that you wish you had collected?

- There were an average of 17 cases per surgeon in your study. Is it possible to show statistical significance for anything given these small numbers?

The devil is in the details, and I hope these come out during the presentation!

Reference: IT’S TIME TO LOOK IN THE MIRROR: INDIVIDUAL SURGEON OUTCOMES AFTER EMERGENT TRUMA LAPAROTOMY. AAST 2021, oral abstract #38.