Let’s continue with my series on the massive transfusion protocol (MTP). I’ll continue today with information on deactivating and analyzing your MTP.

Deactivation. There are two components to this: recognizing that high volume blood products are no longer needed, and communicating this with the blood bank. As bleeding comes under surgical control, and CBC and clotting parameters (and maybe TEG/ROTEM) normalize, the pace of transfusion slows, and ultimately stops. Until this happens, the MTP must stay active. Even a low level of product need should be met with coolers stocked with the appropriate ratios of products.

There are two ways to stop the MTP: the surgeon or their surrogate calls the blood bank (when no more blood products are to be used), or the blood bank calls the surgeon after the next cooler has been waiting for pickup for a finite period of time. This is typically about 30 minutes. It is extremely helpful if the exact deactivation time is recorded in the electronic medical record. However, this information can be obtained from the blood bank.

Analysis. It’s all over, and now the real fun begins. For most trauma centers, the blood bank maintains extensive data about every aspect of each MTP event. They record what units were released and when, when they were returned, which ones were used, were they at a safe temperature on return or were they wasted, and much, much more! Typically, one of the blood bank supervisors or a pathologist then compiles and reviews this data. What happens next varies by hospital.

Ideally, the information from every MTP activation gets passed on to the trauma program. Presentation at your transfusion committee is fine, but this data is most suitable for presentation at the trauma operations committee. And if significant variances are present (e.g. product ratios are way off) then it should also be discussed at your multidisciplinary trauma PI committee as well.

There are relatively few standard tools out there that allow the display of MTP data in an easily digestible form. Here are some of the key points that must be reviewed by the trauma PI program:

- Demographics

- Components used (for ratio analysis)

- Lab values (INR, TEG, Hgb, etc)

- Logistics

- Waste

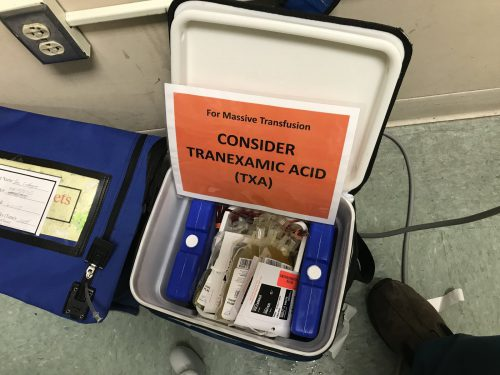

I am aware of two tools, the Broxton form and an MTP audit tool from the Australian National Blood Authority. The Broxton tool covers all the basics and includes some additional data points that cover activation criteria, TXA administration, and administration of uncrossmatched blood. Click here to check it out. The Australian tool is much more robust with more data points that make a lot of sense. You can download a copy by clicking here.

In the next post, I’ll continue with activation criteria for the MTP.