In my last post, I reviewed a very recent prospective study on using CT scan alone for cervical spine clearance in intoxicated patients. I believe that this is the final piece in the spine clearance puzzle to allow us to perform this task intelligently.

We’ve been accumulating more and more data that supports the use of CT scan in patients who fail clinical clearance. This failure can be due to the patient being obtunded or intoxicated, bearing a “distracting” injury, or being just plain uncooperative. Because of this, and our fear of missing a potentially devastating injury (typically because of rare anecdotal cases or urban legends), we have resorted to a significant degree of overkill. This has included, over the years, prolonged immobilization in a rigid collar, flexion/extension imaging (plain x-ray or fluoro), and MRI.

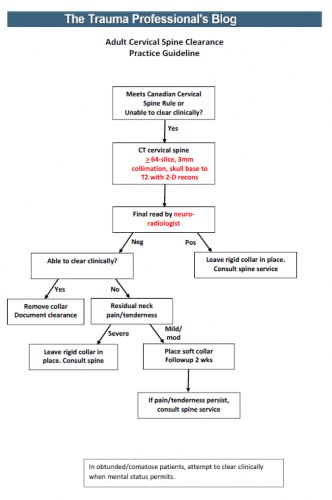

I’ve synthesized the available literature, and have drafted a simple, one sheet practice guideline for discussion. In order to use it, you must have the following:

- A decent CT scanner – minimum 64 slice

- A well-defined scan setup protocol – 3mm collimation, skull base to T2, 2-D reconstruction in sagittal and coronal planes (get a copy of our protocol below)

- A skilled radiologist – neuroradiologist required

An image of the protocol can be found at the bottom of this post. I’m interested in your comments, and your comfort or discomfort with adopting something like this. Please leave comments here or on twitter.

Links:

- New, proposed universal cervical spine clearance practice guideline

- CT scan protocol for performing cervical spine clearance scan

Reference: Cervical spine evaluation and clearance in the intoxicated patient: A prospective Western Trauma Association Multi-Institutional Trial and Survey. J Trauma 83(6):1032-1040, 2017.