ED thoracotomy can be a dramatic, life-saving procedure. From the patient’s perspective, there is only an upside to performing it; without it there is 100% mortality. But to trauma professionals, there is considerable downside risk, including accidental injury, disease transmission and wasted resources. What is the societal risk/cost if ED thoracotomy is performed for weak indications?

The trauma group at Sunnybrook in Toronto looked at this question by retrospectively reviewing 121 patients who underwent the procedure over a 17 year period. They looked at appropriateness, resource use and the safety of the trauma professionals involved. They used the following criteria to determine appropriateness:

- Blunt trauma with an ED arrival time < 5 minutes

- Penetrating torso injury with an ED arrival time < 15 minutes with signs of life

Most of the patients were young men (avg age 30) with 78% penetrating injury and 22% blunt. About half (51%) underwent thoracotomy for inappropriate indications. The vast majority of inappropriate cases were for penetrating injuries with long transport times. Only 3 of the inappropriate thoracotomies were for blunt trauma, yet 24 of the “appropriate” procedures were done in the face of blunt trauma.

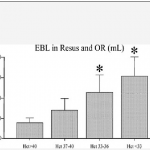

Resource use in the 63 inappropriate cases included 433 lab tests, 14 plain images and 9 CT scans (!!!?), 6 cases in the OR, 244 units of packed red cells and 41 units of plasma. Accidental needlestick injuries occurred in 6% of the inappropriate thoracotomies. None of the patients receiving inappropriate thoracotomy survived.

Bottom line: ED thoracotomy remains a very dangerous procedure. I’ve previously written about guidelines to determine which ones are appropriate (see link below). In this study, many of the procedures were performed on patients with blunt trauma. That means that the number of inappropriate thoracotomies would have been much higher if today’s standards had been applied. So use the guidelines and save your own health, safety and hospital resources. Is it really worth it if you know the patient will not survive?

Related posts:

- Practice guideline for ED thoracotomy

- Video: ED thoracotomy (graphic)

- Technique I: getting in the chest

- Technique II: the heart

- Technique III: clamping the aorta

Reference: Societal costs of inappropriate emergency department thoracotomy. J Amer Col Surg 214(1):18-26, 2012.