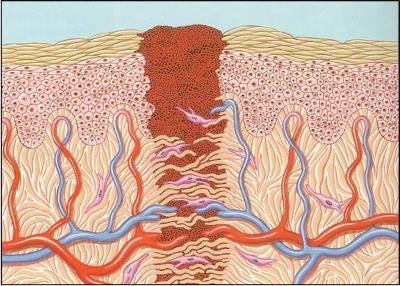

One of the critical maneuvers that EMS providers perform is establishing initial vascular access. This IV is important for administering medications and for initiating volume resuscitation in trauma patients. Prehospital Trauma Life Support guidelines state that every trauma patient should receive two large bore IV lines. But is this really necessary?

The upside of having two IVs in the field is that the EMS provider can give lots of volume. However, a growing body of literature tells us that pushing systolic blood pressure up to “normal” levels in people (or animals) with an uncontrolled source of bleeding can increase mortality and hasten coagulopathy.

The downside of placing two lines is that it is challenging in a moving rig, sterility is difficult to maintain, and the chance of a needlestick exposure is doubled. So is it worth it?

A group at UMDNJ New Brunswick did a retrospective review of 320 trauma patients they received over a one year period who had IV lines established in the field. They found that, as expected, patients with two IVs received more fluid (average 348ml) before arriving at the hospital. There was no increase in systolic blood pressure, but there was a significant increase in diastolic pressure with two lines. The reason for this odd finding is not clear. There was no difference in the ultimate ISS calculated, or in mortality or readmission.

Bottom line: This study is limited by its design. However, it implies that the second field IV is not very useful. The amount of extra fluid infused was relatively small, not nearly enough to trigger additional bleeding or coagulopathy. So if another IV does not deliver significant additional fluid and could be harmful even if it did, it’s probably not useful. Prehospital standards organizations should critically look at this old dogma to see if it should be modified.

Reference:

- Study of placing a second intravenous line in trauma. Prehospital Emerg Care 15:208-213, 2011.