The blood pressure cuff is one of those devices trauma professionals don’t give a second thought to. Old timers like me remember using the cuff with a sphygmomanometer and stethoscope to get manual blood pressures. I’ve had to do this twice in recent months on airplanes, and I had forgotten how much work this is.

But technology makes things easier for us. Now you just slap a cuff on the arm (or wrist), push a button, and voila! You’ve got the pressure.

But have you stopped to think about how this actually works? Why don’t we need the stethoscope any more? Here’s the scoop:

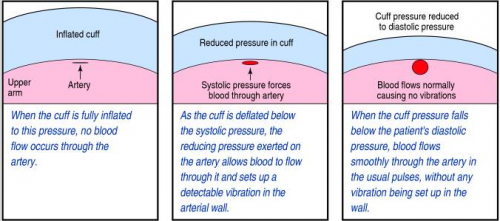

When you take a manual blood pressure, the cuff is inflated until a pulse can no longer be auscultated with the stethoscope. The pressure is slowly released using a little thumb wheel while listening for the pulse again. The pressure at which it is first audible is the systolic, and the pressure at which it softens and fades away is the diastolic.

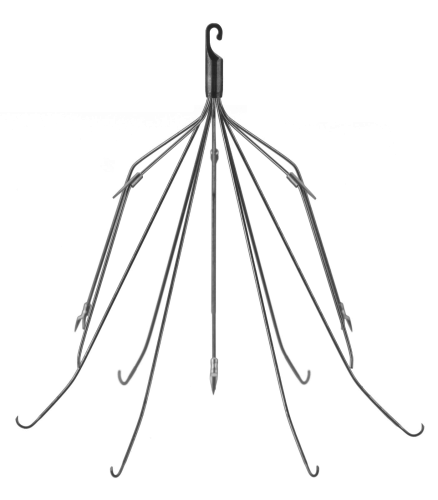

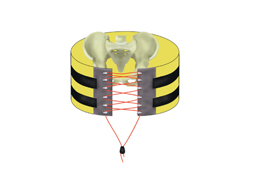

The automatic blood pressure device consists of a cuff, tubing that connects it to the monitor, a pressure transducer in line with the tubing, a mini air pump, and a small computer. The transducer replaces the analog pressure gauge, and the pump and computer replace the human.

The transducer can “see” through the tubing and into the cuff. It is very sensitive to pressure and pressure changes. The computer directs the pump to inflate to about 20 torr above the point where pulsations in the air column cease. It then releases the pressure at about 4 torr per second, “feeling” for air column vibrations to start. When this occurs, the systolic pressure is recorded. Deflation continues until the vibrations stop, representing the diastolic pressure.

Piece of cake! But here’s the question: is it accurate? Tomorrow, I’ll write about how the automated cuff compares to an indwelling arterial line.

Related post: