Over the years I’ve seen a number of trauma professionals, both surgeons and emergency physicians, order liver transaminases (SGOT, SGPT) and bilirubin in patients with liver laceration. I’ve never been clear on why, so I decided to check it out. As it turns out, this is another one of those “old habits die hard” phenomena.

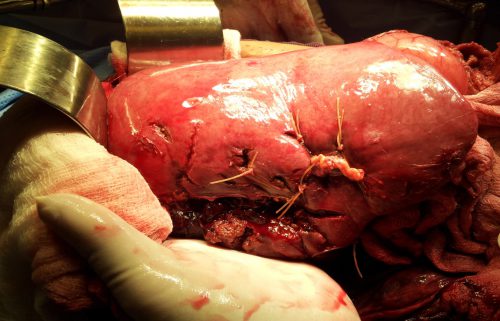

Liver lacerations, by definition, are disruptions of the liver parenchyma. Liver tissue and bile ducts of various size are both injured. Is it reasonable to expect that liver function tests would be elevated? A review of the literature follows the typical pattern. Old studies with very few patients.

From personal hands-on observations, the liver tissue itself tears easily, but the ducts are a lot tougher. It is fairly common to see small, intact ducts bridging small tears in the substance of the liver. However, larger injuries can certainly disrupt major ducts, leading to major problems. But I’ve never seen obstructive problems develop from this injury.

A number of papers (very small, retrospective series) have shown that transaminases can rise with liver laceration. However, they do not rise reliably enough to be a good predictor of either having an injury, or the degree of injury. Similarly, bilirubin can be elevated, but usually not as a direct result of the injury. The most common causes are breakdown of transfused or extravasated blood, or from critical care issues like sepsis, infection, and shock.

Bottom line: Don’t bother to get liver function tests in patients with known or suspected injury. Only a CT scan can help you find and/or grade the injury. And never blame an elevated bilirubin on the injury. Start searching for other causes, because they will end up being much more clinically significant.

References:

- Evaluation of liver function tests in screening for intra-abdominal injuries. Ann Emerg Med 20(8):838-841, 1991.

- Markers for occult liver injury in cases of physical abuse in children. Pediatrics 89(2):274-278.

- Combination of white blood cell count with liver enzymes in the diagnosis of blunt liver laceration. Am J Emerg Med 28(9):1024-1029, 2010.