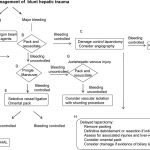

Algorithm For Nonoperative Management of Blunt Hepatic Trauma

Yesterday, I posted the Western Trauma Association’s algorithm for operative management of blunt liver trauma. Click here to view it. Today, I’m going to discuss their algorithm for nonoperative management.

The algorithm is fairly self-explanatory. Click on the image above to read the annotated text for details on each step. Note: this requires full access to the Journal of Trauma.

Some key points in this algorithm:

- Unstable patients need rapid identification of the cause. If the FAST is positive ©, then you need to go to the OR and use the operative algorithm.

- CT scan is used for diagnosis in stable patients (F), but if a liver injury is seen and they become unstable at any time, go to the OR.

- Contrast extravasation in a stable patient should prompt an evaluation and possible embolization by interventional radiography (G).

- If complications develop (SIRS, abdominal pain, fever, jaundice), a repeat CT is indicated (K).

- Abscesses and focal collections of bile may be managed by interventional radiology (L,M). Persistent bile leak may be decreased by ERCP and sphincterotomy (O).

- Bile ascites or large hemoperitoneum may be managed using laparoscopy with drainage (N).

Reference: Western Trauma Association critical decisions in trauma: nonoperative management of adult blunt hepatic trauma. J Trauma. 67:1144–1148, 2009.