In my last post, I discussed a paper describing the incidence of colonic pseudo-obstruction (CPO), or Ogilvie syndrome, in trauma patients. The paper confirmed my bias that this condition could be a problem in a specific subset of trauma patients. They are generally older men with pelvic or spine fractures, with or without surgical fixation. In addition, some comorbidities like diabetes, obesity, and concomitant head injury increase the incidence.

The usual dogma is that a cecal diameter > 12cm places the patient at risk of perforation. Therefore, as the size of the colon increases, steps should be taken to decompress it definitively. This typically involves neostigmine infusion, which usually requires transfer to the ICU, or colonoscopic decompression.

Until about eight years ago, we managed this issue at Regions Hospital using the IV neostigmine option in the ICU. But then, one of our colorectal surgeons described his experience managing CPO with subcutaneous neostigmine. A light bulb turned on! Intravenous neostigmine requires admission to an ICU at our hospital for continuous monitoring to quickly identify the development of bradycardia.

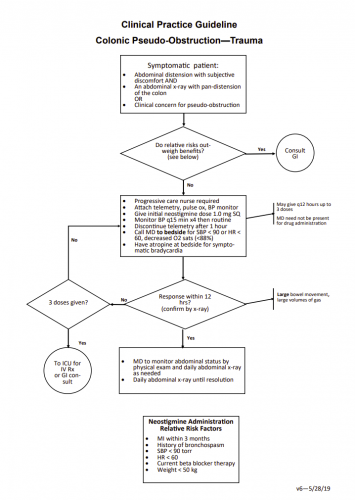

But subcutaneous neostigmine was not on the naughty list! We developed a practice guideline to identify and exclude patients for whom this drug was contraindicated. And it required monitoring that could be accomplished in a floor bed with brief episodes of continuous EKG monitoring. Our inpatient trauma unit could easily do this. However, it might require a step-down bed in yours.

Here is the guideline. Click the image of the link at the end of this post to download a copy.

Here are the major features of the guideline:

Here are the major features of the guideline:

- Identification. Any patient, especially those with the previously described risk factors, begins daily monitoring with a flat plate abdominal x-ray. Patients with abdominal distension with subjective discomfort or nursing concerns with the distension fall into this category.

- Trigger. Once distension of any part of the colon, particularly the cecum, exceeds 10 cm, it is time to act. Otherwise, daily monitoring and a bowel regimen continue.

- Contraindications to neostigmine. If the patient has a recent history of MI, bronchospasm, is on beta-blocker therapy, or has SBP < 90 torr, heart rate < 60, or weight < 50kg, colonoscopic decompression should be carried out.

- Continuous monitoring must be available for one hour after injection. This requires an appropriate nurse and an EKG monitor. Atropine must be present at the bedside in case bradycardia develops.

- Up to three doses of SQ neostigmine (1mg) can be given 12 hours apart. If the patient responds with a large bowel movement or passage of gas, it should be confirmed with an abdominal x-ray.

- Patients with insufficient response must transfer to ICU for IV neostigmine or should be scheduled for an urgent colonoscopy.

Our experience has shown that this guideline is usually very effective. However, a few patients have had a recurrence after 24-48 hours, which is uncommon. The guideline can be repeated if necessary.

Bottom line: A low index of suspicion for CPO in trauma patients is critical. Once the colon perforates, these patients do poorly, and serious complications are common. This guideline allows the trauma service to keep these patients out of the ICU while treating it. But before you implement this, please work closely with your pharmacists to ensure that hospital policy allows using neostigmine outside of an ICU setting.

Colonic Pseudo-Obstruction in Trauma – Practice guideline. Click to download.