We all know that hemoglobin / hematocrit drop after blood loss. We can see it decreasing over the days after acute bleeding or a major operative procedure (think orthopedics). And we’ve been told that the hemoglobin value doesn’t drop immediately after acute blood loss.

But is it true? Or is it just dogma?

A reader sent me a request for some hard references to support this. When I read it, I knew I just had to dig into it. This is one of those topics that gets preached as dogma, and I’ve bought into it as well.

Now, I have personally observed both situations. Long ago, I had a patient with a spleen injury who was being monitored in the ICU with frequent vital signs and serial blood draws (but I don’t do that one anymore). He was doing well, then became acutely hypotensive. As he was being whisked off to the OR, his most recent hemoglobin came back at 10, which was little changed from his initial 11.5 and certainly no independent reason to worry.

But hypotension is a hard fail for nonoperative solid organ management. In the OR, anesthesia drew another Hgb at the end of the case, and the value came back 6.

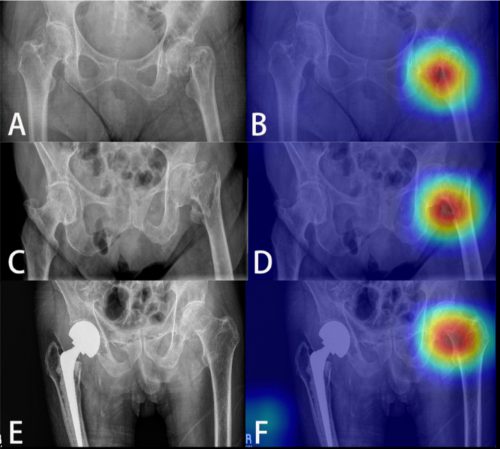

Similarly, we’ve all taken care of patients who have had their pelvis fixed and watched their Hgb levels drop for days. Is this anecdotal or is it real? The doctor / nursing / EMS textbooks usually devote about one sentence to it, but there are no supporting references.

I was only able to locate a few older papers on this. The first looked at the effect of removing two units of red cells acutely. Unfortunately, the authors muddied the waters a little. They were only interested in the effect of the lost red cell mass on cardiac function, so they gave the plasma back. This kind of defeats the purpose, but it was possible to see what happened to Hgb levels over time.

Here were there findings over time for a group of 8 healthy men:

| Time |

Hbg level |

| Before phlebotomy |

14.4 |

| 1 week after |

11.7 |

| 4 weeks after |

12.6 |

| 8 weeks after |

13.6 |

| 16 weeks after |

13.9 |

So the nadir Hgb value occurred some time during the first week after the draw and took quite some time to build back up from bone marrow activity.

That’s the longer term picture for hemoglobin decrease and return to normal. What about more acutely? For this, I found a paper from a group in Beijing who was trying to measure the impact of Hgb loss from a 400cc blood donation on EEG patterns. Interesting.

But they did do pre- and post-donation hemoglobin values. They found that the average Hgb decreased from 14.0 to 13.5 g/dl during the study, which appeared to be brief. Unfortunately, this was the best I could find and it was not that helpful.

Bottom line: Your patient has lost whole blood. So, in theory, there should be no Hgb concentration difference at all. But our bodies are smart. The kidneys immediately sense the acute hypovolemia and begin retaining water. The causes ongoing hemodilution within seconds to minutes. Additionally, fluid in the interstitial space begins to move into the vascular space to replace the volume lost. And over a longer period of time, if no additional fluid is given the intracellular water will move out to the interstitium and into the vascular space.

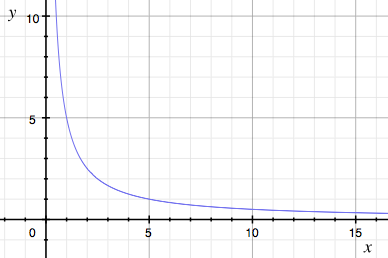

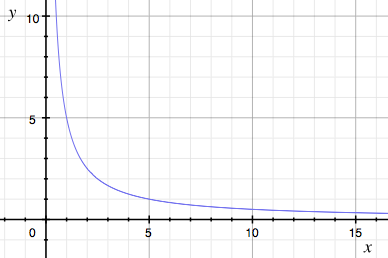

But these things take time. There is an accelerating curve of hemodilution that takes place over hours. The slope of that curve depends on how much blood is lost. A typical 500cc blood transfusion will cause a 0.5 gm/dl drop over several minutes to an hour. We don’t have great data on the exact time to nadir, but my clinical observations support a hyperbolic curve that reaches the lowest Hgb level after about 3 days.

Unlike this curve, it levels off and slowly starts to rise after day 3-4 due to bone marrow activity.

The steepness of the curve depends on the magnitude of the blood loss. After a one unit donation, you may see a 0.5 gm/dl drop acutely, and a nadir of 1 gm/dl. In the case of the acutely bleeding patient with the spleen injury, the initial drop was 1.5 gm/dl. But two hours later it had dropped by over 5 gm/dl.

Unfortunately, the supporting papers are weak because apparently no one was interesting in proving or disproving this. They were more interested in cardiac function or brain waves. But it does happen.

Here’s the takeaway rule:

In a patient with acute bleeding, the initial hemoglobin drop is just the tip of the iceberg. Assume that this is only a third (or less) of how low it is going to go. If it has fallen outside of the “normal” range, call for blood. You’ll need it!

References:

- Effect on cardiovascular function and iron metabolism of the acute removal of 2 units of red cells. Transfusion 34(7):573-577, 1994.

- The Impact of a Regular Blood Donation on the Hematology

and EEG of Healthy Young Male Blood Donors. Brain Topography 25:116-123, 2012.