Placing the chest tube collection system to water seal can be a valuable tool in determining if it’s time to remove the tube. The idea is that removing suction from the system will help identify a slow air leak that may not be obvious while watching the collection system. Typically, water seal without suction is maintained for 6 hours and a chest xray is obtained to look for a new (or larger) pneumothorax.

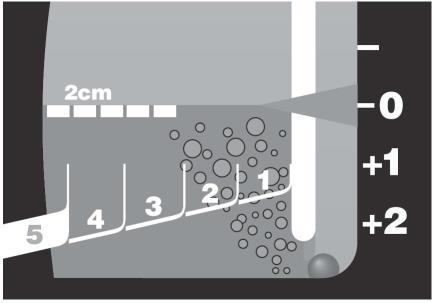

Here’s a way to detect a small air leak faster. When you enter the patient room, disconnect the suction tubing from the collection system. Chat with your patient, and do your usual thorough exam. Take your time. When you are done, slowly slip the suction tubing back onto the collection system. Watch the water seal chamber closely for any bubbles that try to sneak under the partition (above).

If the fluid level slowly lowers, but no bubbles pass the partition, there is no significant leak. On occasion, I’ve seen a single bubble creep under, and this is probably okay. However, if a train of bubbles passes, an air leak is present and it is premature to consider pulling the tube. Place the system back on suction.

Like so many tests, this one is only helpful if a leak is seen. It means that a significant amount of air has accumulated in the short time you’ve been examining your patient. If there are no bubbles, there still could be a very slow leak, so they will still need a formal water seal test, if indicated. See the protocol below for details.

Related post: