There is an ongoing debate over the differences between Level I vs Level II trauma centers in the US. On paper, the major differences include resident rotations in trauma, research, and the available of certain specialty surgeons and services. There have been several papers that look at survival differences between the two levels.

One podium paper at AAST 2018 re-examines this debate. It is a medium-sized pooled series that looks at a particular type of injury, pelvic ring fractures. These injuries can be complex, and many times require specialized orthopedic expertise. ACS Level I centers are required to have at least one Orthopedic Trauma Association fellowship-trained surgeon among their orthopedists. This is not required for Level II centers, but many do have them.

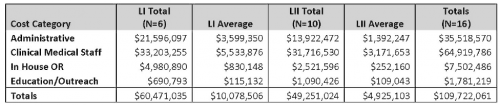

The group at the University of Michigan examined patients with partially stable or unstable pelvic ring injuries in a trauma collaborative database including 29 Level I and Level II centers over a 7-year period. They used propensity matching to compare 610 patients admitted to Level I and 610 patients admitted to Level II centers with these injuries:

Here are the factoids:

- Mortality was significantly increased at Level II centers ( 12%) vs Level I centers (8%)

- Angiography was used significantly less at Level II centers (6% vs 11%)

- Complex repairs were used significantly less frequently at Level II centers (32% vs 42%)

- Patients were significantly less likely to be admitted to an ICU at Level II centers, and were more often admitted to stepdown units (45% vs 52%)

- Failure to rescue rate was lower (better) in ICU patients

Bottom line: Obviously, there are some limitations to using this pooled data, but it does provide larger numbers than many similar papers have. It cannot distinguish Level II centers that have OTA-trained orthopedic surgeons from those that do not. But the results are rather striking. It’s not clear exactly which of the institutional differences might be responsible for the improved mortality, and they all probably contribute to some degree. But the abstract appears to show that Level II centers are not just non-academic Level Is. This work suggests that certain injury patterns really should be transferred to a center with the specialized resources to treat it well.