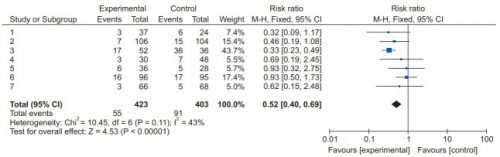

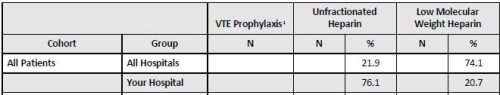

We’ve learned a couple of things in the last two posts by reviewing recent systematic review / meta-analysis studies. First, low molecular weight heparin provides better prophylaxis against venous thromboembolism (VTE) than unfractionated heparin. And giving prophylaxis within the first 72 hours of admission significantly decreases the incidence of VTE with no increase in existing intracranial bleeds or mortality.

So the only remaining question is, how low can you go? That is, how soon can you safely start chemoprophylaxis? The trauma group at George Washington University in DC put together a study to examine this question.

They, and one other Level I trauma center, performed a retrospective cohort study of adult, blunt TBI patients over a three year period. Patients with penetrating brain injury, and those with any other body region with significant injury (AIS >1) were excluded so this group truly represented isolated brain injury. Other exclusion criteria were progression of blood on CT within 6 hours, and crani or death within 24 hours. Early VTE prophylaxis was defined as occurring within 24 hours, and late was > 24 hours.

All patients had hourly neuro evaluations and a repeat head CT at six hours after admission. All had compression devices applied to their legs, and received either low molecular weight (LMWH) or unfractionated heparin (UH) at a fixed dose regarding of body habitus. Anti-Factor Xa levels were not measured.

Here are the factoids:

- Between the two centers, 264 met inclusion criteria

- About 40% received early prophylaxis and the remaining ones received their drug after 24 hours

- ISS was higher (18 vs 15) and GCS was lower (13 vs 14) in the late therapy group

- About 88% of patients in the early prophylaxis group received LMWH vs only 63% in the late group

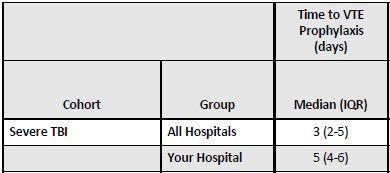

- Average time to prophylaxis start in the early group was 17 hours vs 47 hours in the late group

- There were no differences in bleed progression between early and late groups (5.6% vs 7%)

- The craniotomy / craniectomy rates were the same in early and late groups (1.9% vs 2.5%)

- VTE rate was the same in early vs late groups (0% vs 2.5%)

Bottom line: The authors concluded that there was no additional risk in giving early VTE prophylaxis in TBI patients with a stable CT seven hours after arrival. This was true for patients with subdural, epidural, subarachnoid, and intraparenchymal bleeds.

But there are some limitations to consider. This was a retrospective study, and was a “how we do it” study” as well in terms of the choice of LMWH vs UH. This means there was not protocol for the form of heparin used; that was determined by surgeon preference.

There was also a difference in ISS and GCS between groups. However, the difference may not have been clinically significant, and it could have made the late group look worse if it were. Statistically, it did not.

And finally, the numbers are small and there was no power analysis. So there is the question of whether a significant difference could have even been detected.

What does it all mean? Well, it suggests that early (within 24 hours) chemoprophylaxis does not cause harm compared to later administration. But the study is not definitive enough to change practice yet. It should definitely prompt discussions and practice guideline development for starting prophylaxis after 24 hours of CT scan stability now. And hopefully these authors (or others) are planning a better prospective study to help us start even sooner!

Reference: Early chemoprophylaxis against venous thromboembolism in patients with traumatic brain injury. Am Surgeon 88(2):187-193, 2021.