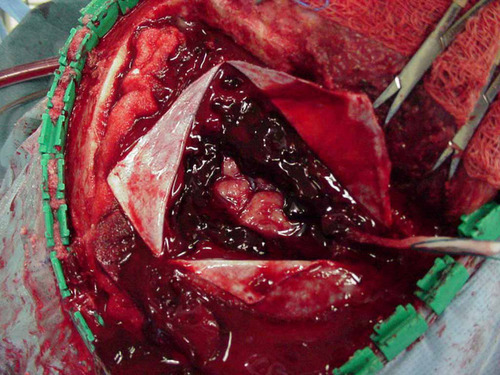

Trauma centers in the US are seeing lots of elderly patients, and falls are a major mechanism in the patient group. A significant number sustain a traumatic brain injury. Extra-axial bleeding is fairly common, but because of the increased space available inside the skull, the patient may not become overtly symptomatic.

So what objective criteria can be used to determine if evacuation of a subdural hematoma (SDH)is needed? A study from the University of Manchester in the UK sought to figure this out. They speculated that the size of the lesion and the amount of displacement it caused might be objective enough. So they set out to see if any specific numbers would provide a reliable method.

Here are the factoids:

- Two neurosurgeons reviewed four years of head CT scans and determined if they should be treated surgically or nonsurgically.

- Measurements of the maximum thickness of the lesion, its volume, and the degree of midline shift were taken.

- Reasonable attempts were made to ensure inter-rater reliability.

- The total pool of scans studied was 483. 44% were judged to need surgical management.

- Maximum SDH thickness of 10mm or more, or a midline shift of 1mm or more were found to accurately predict 100% of surgical lesions.

- The best predictor of the need for surgery was midline shift.

- Adding hematoma thickness did not significantly improve the ROC curve.

Bottom line: This study is somewhat limited because it is the experience of only one hospital, and the number of clinicians involved in decision making is small. It does echo other similar studies, but in my opinion it omits the use of the mental status exam.

Using a lesion thickness of 10mm or shift of 1mm does not necessarily mean the patient needs surgery if there mental status is completely normal. But these criteria can certainly identify a subset of patients who are at risk, and should be monitored very carefully for any deterioration. A change in GCS by even a single point should then send them straight to OR.

Related posts:

Reference: A simple tool to identify elderly patients with a surgically important acute subdural haematoma. Injury 46(1):76-79, 2015.