Earlier this year, there were a lot of television commercials for Prevnar 13, a 13-valent pneumococcal vaccine for immun-ocompromised or asplenic adults. And interestingly, I noticed that the CDC has added a recommendation that these patients receive this vaccination, followed by the original 23-valent vaccine (Pneumovax 23) 8 weeks later.

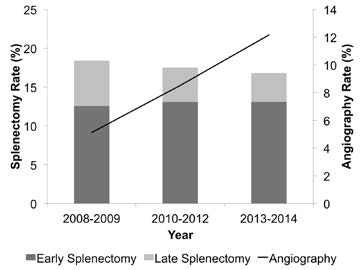

WTF? Patients with splenectomy (or significant angio-embolization) for trauma are considered functionally asplenic. And although the data for immunization in this group is weak, giving triple vaccinations with pneumcoccal, H. flu, and meningococcal vaccines has become a standard of care.

This was difficult enough already because there was debate around the best time to administer: during the hospital stay or several weeks later after the immune system depression from trauma had resolved. The unfortunate truth is that many trauma patients never come back for followup, and so don’t get any vaccines if they are not given during the hospital stay.

And then came the recommendation a few years ago to give a 5-year booster for the pneumococcal vaccine. I have a hard time remembering when my last tetanus vaccine was to schedule my own booster. How can I expect my trauma patients to remember and come back for their pneumococcal vaccine booster?

So what do we do with the CDC Prevnar 13 recommendation? If we add it, it means that we give Prevnar while the patient is in the hospital, and then hope they come back 8 weeks later for their Pneumovax. And then 5 years later for the booster dose. Huh?

Looking at the package insert, I read that Pneumovax 23 protects against 23 serotypes of S. Pneumo, which represent 85% of most commonly encountered strains out there. So it’s not perfect. Prevnar 13 protects against 13 serotypes, and there is no in-dication as to what percent of strains encountered are protected against.

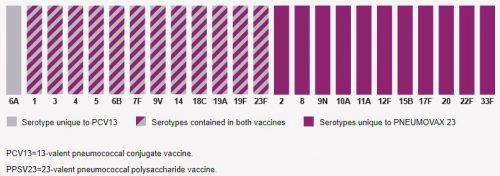

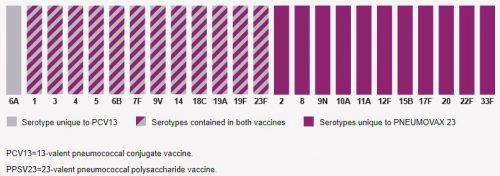

So I decided to dig deeper and look at the serotypes included in each vaccine. They are shown in the chart below. The 23 bars with maroon in them (solid or striped) are Pneumococcal serotypes covered by Pneumovax 23. The 13 bars containing gray are ones covered by Prevnar 13. There is only one serotype in Prevnar 13 not covered by Pneumovax 23, serotype 6A. Unfortunately, it’s nearly impossible to find the prevalence of infections by serotype, and it varies geographically and over time anyway. So does cover-age of a single extra serotype by Prevnar 13 justify an additional vaccination and complicated administration schedule? Hmm.

It turns out that there is one significant difference between these two vaccines. Pneumovax 23 is a polysaccharide vaccine made up of fragments of polysaccharide from pneumococcus cell walls. Prevnar 13 is a “conjugated vaccine,” meaning that the polysaccharides are linked to a protein. This is thought to increase the immune system response to the vaccine.

(click for full-size graph)

(click for full-size graph)

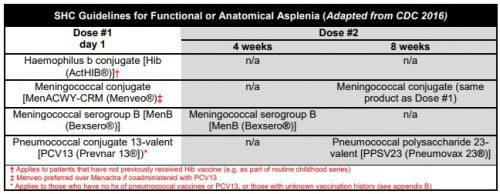

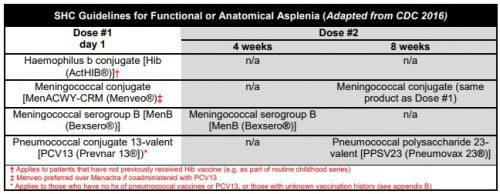

The current CDC recommendations are listed below. In the old days, we just gave three vaccines before the patient left the hospital. Then the Pneumovax 23 booster was added at 5 years. Same for the meningococcal serogroup B booster at 4 weeks. Then the meningococcal conjugate vaccine (Menactra) came along and was added (with a booster at 8 weeks). Finally, Prevnar 13 was added with its own booster, and Pneumovax 23 was delayed for 8 weeks. Oh, and don’t forget the 5 year boosters for both Pneumovax 23 and the meningococcal conjugate vaccines. It has become very complicated.

(click for full-size chart)

(click for full-size chart)

In my next post, I’ll try to make sense of this mish-mash and offer some thoughts on how to decide what to do for your patients.