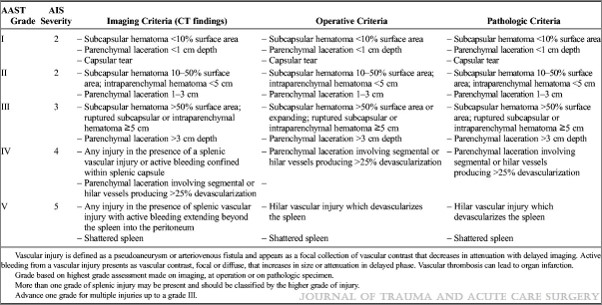

Nearly 20 years ago, the American Pediatric Surgical Association (APSA) published a clinical guideline for management of solid organ injury in children. Part of the guideline included activity restrictions, specifically for a period of time after injury. This was generalized by many clinicians to include a period of in-hospital bed rest.

A paper has just been published that examines the usefulness of restricting activity in pediatric patients with solid organ injury. It was authored by a consortium of 10 Level I pediatric trauma centers, and included all patients through age 18 who did not have a concomitant significant renal injury and no pancreatic injury. All injuries were diagnosed by CT scan over a 33 month period.

Activity restrictions were given to all patients upon discharge, which limited sports, wheeled recreational activities, and anything else requiring two feet off the ground. A phone survey was conducted 60 days post-discharge to judge compliance. Unplanned return to ED, readmission, and complications were also assessed.

Here are the factoids:

- A total of 1007 patients were studied, and 99 were excluded due to concomitant pancreatic or high grade renal injury. An additional 79 were excluded due to missing injury grade or operative management.

- Of the remaining patients, only 366 were available for 60-day followup

- 279 claimed to adhere to activity restrictions; 13% returned to the ED and 6% were readmitted.

- 49 admitted that they did not pay attention to the restrictions, and only 4 (8%) returned to the ED. None were hospitalized.

- Even in the high-grade injury patients, there was no difference between compliant or noncompliant groups

- No patient in either group bled post-discharge

Bottom line: Due to the nature of this study (specifically the phone survey component), there will be degradation of the data. Some patients do not want to admit that they didn’t follow the doctor’s orders. In theory, this could increase the number of complications / returns to ED in the “compliant” group. But it did not.

The other issue I have with this study is that it was not stratified by age. The spleen of an 18 year old is very different than that of a 6 year old. Sixty years ago, we used to take spleens out in adults with a diagnosed injury. The reason we moved toward nonoperative management in adults was the very favorable experience we had in children. Unfortunately, nowhere in this paper is age broken out. Typically, the number of older children (who are really adults) with the injury far outnumber the younger ones, which also tends to increase the number of complications seen. But once again, we did not. Small numbers? Possibly.

So what are we to make of all this? Basically, it tells us that we’ve been trying to restrict activity in our patients with liver and spleen injury for no good reason. And this applies especially to the children. Look at your own clinical experience, and try to recount how many “failures” you’ve seen due to failure to follow activity restrictions. More typically, failures are due to undiagnosed or untreated pseudoaneurysms.

It’s time to rethink your solid organ management protocol, if you haven’t already. Do you really need a period of NPO status? Or bedrest? Or activity restriction? And have you ever tried to restrict activity in a 6-year old? Have a look at the guideline we’ve used at my hospital for nearly 20 years! We got rid of the NPO and bedrest restrictions a while ago. Now it’s time to start reducing the activity restrictions!

References:

- Evidence-Based Guidelines for Resource Utilization in Children With

Isolated Spleen or Liver Injury. J Ped Surg 35(2):164-169, 2000.

- Adherence to APSA activity restriction guidelines and 60-day clinical outcomes for pediatric blunt liver and splenic injuries (BLSI). J Ped Surg in Press, 2018.

Click to download larger image

Click to download larger image