Back in the day, the only way to fix a broken thoracic aorta was via left thoracotomy. This was a big procedure, with the possibility of several major complications, with postop paraplegia being one of them. At the time, there was a debate about whether the procedure should be done immediately versus waiting until the patient was well-resuscitated. The concern was that death was nearly certain if the aortic lesion progressed.

We learned that temporizing with strict blood pressure control worked wonders at protecting the patient. Although many of these injuries were managed within hours, a growing number were delayed by a few days to improve outcomes.

Nowadays, thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR) is routine and much less morbid than the open procedure. However, the same question arises: do it early or wait a while? Interestingly, not one but two analyses have been published on this very topic in the last four months!

The first is from an international research group that searched the usual databases and initially found 921 records. They included only clinical trials or cohort studies with ten or more adult patients that could be stratified as early (within 24 hours) or late (after 24 hours) intervention. After applying these criteria, only seven studies remained for analysis.

There were 3,757 patients with early repairs, compared to 1,238 undergoing late repair. The presenting demographics and injury grades were similar in each group. However, the short-term mortality was significantly higher (1.9x) in the early TEVAR group. Additionally, ICU length of stay was significantly longer (3 days) in the late TEVAR group.

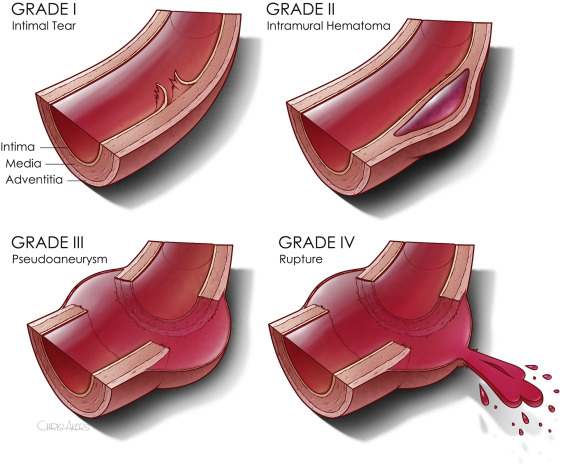

The second paper was presented as a quick-shot at last year’s AAST meeting. It is from a group of researchers from our big Boston trauma centers and the Netherlands. They used four years of data from the TQIP database, giving them extra information unavailable in the first study. They specifically looked at patients with grade II or III injuries. Here is the grading scale:

Here are the factoids:

- A total of 1,339 patients were studied, with about three-quarters in the early TEVAR group

- Median time to TEVAR was 4 hours in the early group and 65 hours in the late group

- Patients in the early group were significantly less likely to have brain or liver injuries

- ISS was similar in both groups

- The early TEVAR group had significantly higher in-hospital mortality (16% vs. 5%), significantly higher risk of ARDS (7.6% vs. 2.1%), but significantly shorter ICU stay (7 vs 10 days)

- When patients who died within the first 24 hours were excluded, the in-hospital mortality remained significantly higher, and the ICU and hospital lengths of stay were significantly shorter

Bottom line: Some society guidelines began recommending delayed TEVAR in 2015. This study did not detect any trend toward this, however. Using different methods and databases, these two studies identified nearly identical mortality and ICU trends in large groups of patients. The mortality trends do not appear to be related to injury grade, overall injury severity, or the presence of head injury.

Taken together, this suggests that we need to rethink the timing of TEVAR in patients with grade II or III injuries. The best timing still needs to be defined, but it appears to be beyond 24 hours. Centers performing this procedure should review their results and consider extending procedure timing as additional research is done to define the ideal time interval.

References:

- Early Versus Delayed Thoracic Endovascular Aortic Repair for Blunt Traumatic Aortic Injury: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cureus. 2023 Jun 28;15(6):e41078. doi: 10.7759/cureus.41078. PMID: 37519486; PMCID: PMC10375940.

- Early Versus Delayed Thoracic Endovascular Aortic Repair for

Blunt Thoracic Aortic Injury: A Propensity Score-Matched Analysis. Ann Surg 278:e848-e854, 2023.