Deep venous thrombosis has been a problem in adult trauma patients for some time. Turns out, it’s a problem in injured children as well although much less common (<1%). However, the subset of kids admitted to the ICU for trauma have a much higher rate if not given prophylaxis (approx. 6%). Most trauma centers have protocols for chemical prophylaxis of adult patients, but not many have similar protocols for children.

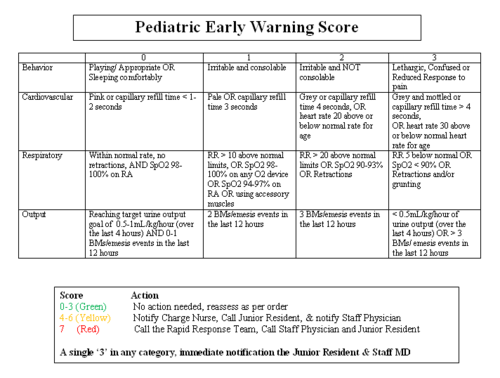

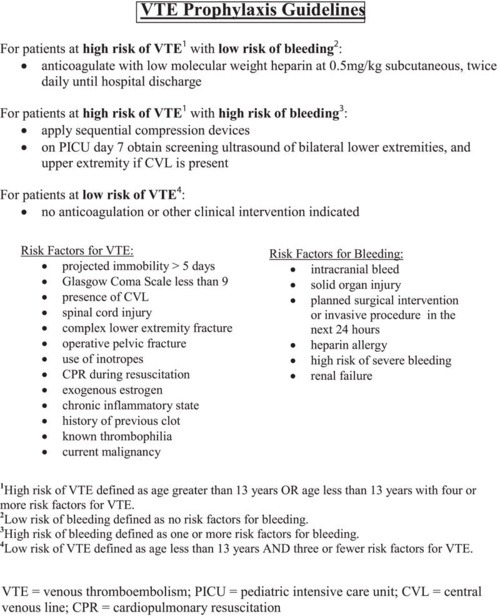

The Medical College of Wisconsin looked at trends prior to and after implementation of a DVT protocol for patients < 19 years old. They used the following protocol to assess risk in patients admitted to the PICU and to determine what type of prophylaxis was warranted:

The need for and type of prophylaxis was balanced against the risk for significant bleeding, and this was accounted for in the protocol. The following significant findings were noted:

- The overall incidence of DVT decreased significantly (65%) after the protocol was introduced, from 5.2% to 1.8%

- The 1.8% incidence after protocol use is still higher than most other non-trauma pediatric populations

- After the protocol was used, all DVT was detected via screening. Suspicion based on clinical findings (edema, pain) only occurred pre-implementation.

- Use of the protocol did not increase use of anticoagulation, it standardized management in pediatric patients

Bottom line: DVT does occur in injured children, particularly in severely injured ones who require admission to the ICU. Implementation of a regimented system of monitoring and prophylaxis decreases the overall DVT rate and standardizes care in this group of patients. This is another example of how the use of a well thought out protocol can benefit our patients and provide a more uniform way of managing them.

Related posts:

- Does central line insertion promote DVT?

- Does interrupting DVT prophylaxis increase risk?

- Microparticles and DVT

- Does pulmonary embolism really arise from DVT?

Reference: Effectiveness of clinical guidelines for deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis in reducing the incidence of venous thromboembolism in critically ill children after trauma. J Trauma 72(5):1292-1297, 2012.