In the previous post in this series, I described an early review article summarizing several older studies comparing these two hemorrhage control techniques for pelvic fractures. Today, I’ll review another paper fresh off the press, published just this month.

This paper comes from the orthopedics and neurosurgical groups at the University of Texas-San Antonio. They scanned five years of data from the National Inpatient Sample, which included data from 35 million inpatient admissions in the US. They separated all patients with acetabular and pelvic ring fractures using ICD-10 codes.

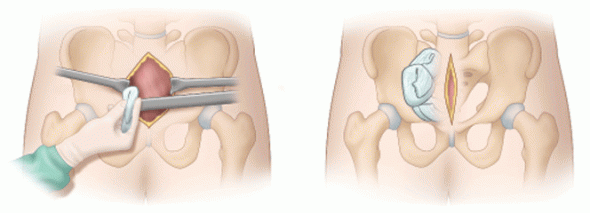

They further narrowed their dataset to patients with angioembolization (AE) or peri-pelvic packing (PPP) as their primary procedure. This eliminated patients who might have received other additional management that could cloud the data. Various hospital outcomes were tabulated, including hospital charges, mortality, and discharge location.

Here are the factoids:

- Of the 3,780 patients identified, only 160 underwent PPP, and the remaining 3,620 had AE. This is probably a function of PPP’s newer and more novel nature.

- The AE patients were significantly older than the PPP patients (66 vs 53 years). This suggests that trauma professionals have a lower threshold to order AE in older patients.

- Time to procedure start was similar for both interventions

- Overall, there was no difference in mortality between the AE and PPP patients

- There was no difference in unfavorable discharge (other than home)

- Hospital charges were significantly lower in the AE group ($369K vs $250K)!

Bottom line: This is the largest comparison of AE and PPP to date. It mostly confirms earlier work and adds significant insights about cost and discharge status.

AE and PPP have equivalent outcomes. This is true even though the AE group is larger and significantly older. However, it is possible that the number of PPP cases was too low for the authors to demonstrate any significant differences.

What should you do when faced with these patients? First, hemodynamic instability means that PPP is the only choice. You can feel comfortable that outcomes will be the same as AE. If there is concern that there could be ongoing bleeding, PPP can be followed by a trip to the interventional radiology suite. This is a common practice.

I shouldn’t have to say it, but AE should never even be considered in an unstable patient.

What about stable patients? AE seems to be the way to go. It is tolerated even by older patients. And it ends up saving a lot of money when compared to PPP.

There is still room for research in this space. As our PPP experience grows, we should hopefully be able to confirm the conclusions in this paper. If any are refuted, I’ll revisit this post and make the needed updates. Which is what you should also do in your practice!

Reference: Angioembolization Has Similar Efficacy and Lower Total Charges than Preperitoneal Pelvic Packing in Patients With Pelvic Ring or Acetabulum Fractures. J Orthop Trauma 38(5):254-258, 2024.