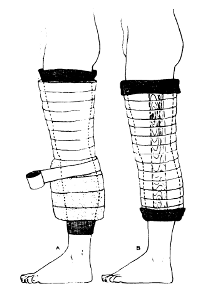

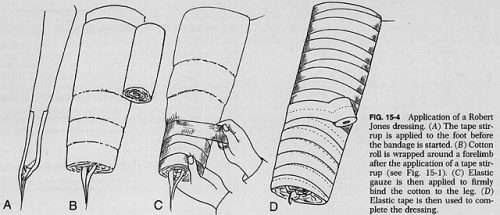

The Robert Jones dressing is a thick, padded bandage classically applied to the thigh and leg. It is thought to reduce swelling by applying even pressure to the extremity, which in turn should promote healing. And since it is a soft dressing, as opposed to a cast, there is less chance of developing skin breakdown from direct pressure. Here’s a compression-type dressing described in 1937 using stockinette, cotton wool, and elastic cloth, although it was not attributed to Jones at that point.

Charnley provided a detailed description of the bandage in 1950, and was the first to refer to Jones.

Interestingly, Robert Jones never really referred to the dressing by name. There were references to a “pressure crepe bandage over copious wool dressing” in his operative logs, but it wasn’t until much later that his name became associated with it. Because of this, the composition of the bandage has varied greatly over time.

But who was Robert Jones? We in the States are fairly ignorant, but my UK readers are very familiar. Jones was a British surgeon who practiced through the late 1800s and past the end of World War I. He learned about fractures from his uncle, and became one of the few surgeons of the time to be interested in fracture care. Until then, orthopaedics was focused primarily on correcting deformities in children. He received his FRCS in 1889. After being appointed Surgeon-Superintendent of the Manchester Ship Canal, he established the first comprehensive accident service in the world to take care of injured workers. He founded the British Orthopaedic Society in 1894, and introduced the concept of military orthopaedic hospitals during World War I. His innovations led to significant decreases in morbidity and mortality from fractures in the war, particularly of the femur.

And does his eponymous dressing actually work? There has been little research in this area. There is one study that I have found that actually measured compartment pressures to see if the loss of edema from compression caused a noticeable pressure decrease. Here are the factoids:

- This was a very small prospective study from 1986 of 9 patients (!) who had just undergone knee arthroplasty

- Slit catheters were placed into the compartment 10 cm below the knee joint (but they didn’t say which compartment)

- Thick cotton-wool from a roll was applied over the surgical dressings twice, each with a thickness of two inches. An elastic bandage was then applied snugly.

- Much to the researchers’ surprise, compartment pressures did not fall as expected over time. They were basically constant until the dressing was removed. Then the pressures fell significantly.

Bottom line: Robert Jones’ fame is well deserved. However, his dressing (which he did not name, and may not even be what he used), did not have the pressure-reducing effect on an injured limb that surgeons thought. No studies on edema and healing have been done. It’s basically a fluffy dressing. However, that is a good thing. It keeps the leg padded, protecting the skin, and immobilized. It’s like a very well padded cast, without the risk of skin breakdown. And because of its simplicity, it will probably be used for quite some time to come.

References:

- The Robert Jones bandage. JBJS 68B(5):776-779, 1986.

- The treatment of fracture without plaster of Paris. Closed Treatment of Common Fractures, E&S Livingstone 1950, pg 28-29.

- Handbook of Orthopaedic Surgery. CV Mosby 1937, pg 418.