There are still many questions regarding optimal management of blunt carotid and vertebral arterial injury (BCVI). We know that they may ultimately result in a stroke. And we kind of know how to manage them to try to avoid this. We also know that the grade may change over time, and many vascular surgeons recommend re-imaging at some point.

But when? There are still many questions. A multi-center trial has been collecting observational data on this issue since 2018. The group reviewed three years of data to examine imaging characteristics and stroke rate during the study period.

Here are the factoids:

- A total of 739 cases were identified at 16 trauma centers

- The median number of imaging studies was 2, with a range of 1-9 (!). Two thirds received only one study.

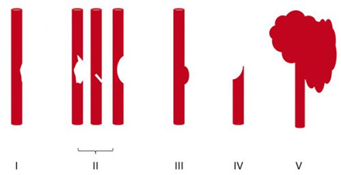

- Injury grade distribution was as follows:

- Grade 1 – 42%

- Grade 2 – 30%

- Grade 3 – 10%

- Grade 4 – 18%

- Grade 5 – <1%

- About 30% changed in grade during the hospitalization, with 7% increasing and 24% decreasing.

- Average time to change in grade was 7 days

- Nearly 75% of those that decreased actually resolved. All of the grade 1 lesions resolved.

- Stroke tended to occur after about one day after admission, although the grade 1 lesions took longer at 4 days

- Strokes occurred much earlier than grade change

The authors concluded that there should be further investigation about the utility of serial imaging for stroke prevention.

Bottom line: This is basically a “how we did it” study to tease out data on imaging and stroke after BCVI. It’s clear that there is no consensus across trauma centers regarding if and when repeat imaging is done. And it’s not really possible to make any recommendations about repeat imaging based on this study.

However, it does uncover one important fact. It takes a week for the injury grade on CT to change, but strokes occur much earlier and usually within 24 hours! This is important because it makes it clear that it’s crucial to actually make the diagnosis early. Average stroke occurrence was 9% overall. Grade 1 injuries had only a 3% rate, but grades 2-4 were in the 12-15% range. Grade 5 had a 50% stroke rate!

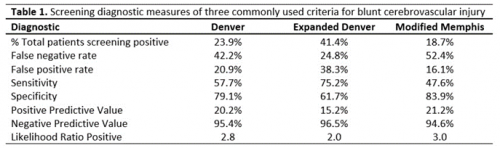

These facts reinforce the importance of identifying as many of these BCVI as possible during the initial evaluation. The abstract I reviewed yesterday confirmed that the existing screening criteria (Memphis, Denver) will miss too many. More liberal imaging is probably indicated. If you missed the post, click here to view it in a new window.

Here are my comments for the authors and presenter:

- The “change in BCVI grade over time” charts in the abstract are not readable. Please provide clear images during your presentation and explain what they mean. I was confused!

- Based on your data, do you have any recommendations regarding the utility of re-imaging? Is it necessary in the same hospitalization at all? These patients will receive treatment anyway, and it doesn’t appear to have any impact on stroke rate.

- Do you have any recommendations regarding the (f)utility of existing screening systems given the early occurrences of stroke in the study? Are you a fan of using energy / mechanism rather than a bullet list of criteria?

This is important work and I can’t wait to look at the data up close.

Reference: BLUNT CEREBROVASCULAR INJURIES: TIMING OF CHANGES TO INJURY GRADE AND STROKE FORMATION ON SERIAL IMAGING FROM AN EAST MULTI-INSTITUTIONAL TRIAL. EAST 35th ASA, oral abstract #34.