Over and over, we hear that children are not just little adults. They are a different size, a different shape. Their “normal” vital signs are weird. Drug doses are different; some drugs don’t work, some work all too well.

But in many ways, they recover more quickly and more completely after injury. What about after what is probably the biggest insult of all, cardiac arrest after blunt trauma? The NAEMSP and the ACS Committee on Trauma recently released a statement regarding blunt traumatic arrest (BTA):

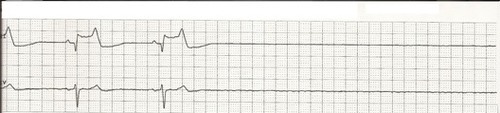

“Resuscitation efforts may be withheld in any blunt trauma patient who, based on out-of-hospital personnel’s thorough primary patient assessment, is found apneic, pulseless, and without organized ECG activity upon arrival of EMS at the scene.“

The groups specifically point out that the guidelines do not apply to the pediatric population due to the scarcity of data for this age group.

The Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles and USC conducted a study of the National Trauma Data Bank, trying to see if children had a better outcome after this catastrophic event. Patients were considered as children if they were up to and including age 18.

Here are the factoids:

- Of 116,000 pediatric patients with blunt trauma, 7,766 had no signs of life (SOL) in the field (0.25%)

- The typical male:female distribution for trauma was found (70:30)

- 75% of those without SOL in the field never regained them. Only 1.5% of these survived to discharge from the hospital.

- 25% regained SOL with resuscitation, and 14% of them were discharged alive.

- 499 patients underwent ED thoracotomy, and only 1% survived to discharge. There was no correlation of thoracotomy with survival.

- It appeared that there was a tendency toward survival for the very young (age 0-4) without SOL, but statistical analysis did not bear this out

Bottom line: Children are just like little adults when it comes to blunt cardiac arrest after trauma. Although it is a retrospective, registry-based study, this is about as big as we are likely to see. And don’t get suckered into saying "but 1.5% with no vital signs ever were discharged!” This study was not able to look at the quality of life of survivors, but there is usually significant and severe disability present in the few adult survivors after this event.

Feel free to try to re-establish signs of life in kids with BTA. This usually means lots of fluid and/or blood. If they don’t respond, then it’s game over. And, like adults, don’t even think about an emergency thoracotomy; it’s dangerous to you and doesn’t work!

Related posts:

- Societal cost of ED thoracotomy

- FAST cardiac ultrasound and traumatic arrest

- Bystander CPR for people not in cardiac arrest

Reference: Survival of pediatric blunt trauma patients presenting with no signs of life in the field. J Trauma 77(3):422-426, 2014.