For the most part, trauma centers are free to pick and choose their own trauma team activation trigger criteria. Typically, these are a mix of physiologic, anatomic, and mechanistic items. However, the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma mandates that either seven (Orange Book) or eight (Gray Book) specific criteria must present in every center’s highest-level activation list.

One of these mandatory criteria is a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of eight or less. The reason is that this level denotes a severe brain injury and as patients approach it they are less and less able to protect their own airway. Although this specific GCS is a minimum, centers are free to choose their own specific threshold as long as it is not any lower.

How does a center choose the “right” GCS? It seems straightforward, right? A mild TBI is defined as GCS from 13-15. These patients have only lost one or two points in their eye-opening, verbal, and motor scores and are relatively unlikely to have a significant lesion in their head or an airway issue.

At the other end of the spectrum is the severe TBI, with a GCS of 3-8. These are a chip shot, with the potential for severe injury and a frequently threatened airway. They demand rapid assessment and intervention, hence the required trauma activation.

But what about those patients with moderate TBI with a GCS from 9-12? They obviously have a higher risk for serious intracranial injury. And as the GCS declines, the patient’s ability to protect their airway decreases. At some point between those GCS scores, most clinicians hit their own internal trigger to provide a definitive airway.

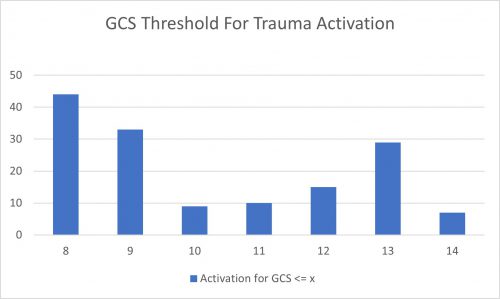

So what do actual trauma centers choose as their threshold? I conducted an informal survey of my readers, asking them to provide their specific GCS threshold.

Here are the factoids:

- A total of 147 trauma centers of all levels responded

- They were located in the United States, Germany, Saudi Arabia, and Singapore

- This chart shows the number of centers that selected a threshold less than or equal to the GCS on the horizontal axis:

- Nearly a third of centers (30%) adhere strictly to the ACS criterion of 8

- Another 22% use a threshold of 9, possibly to avoid any confusion from having a “less than or equal to” criterion

- There is another bump on the curve at 13, with 20% using this threshold

Bottom line: A little more than half of centers use a GCS threshold of 8 or 9 as their TTA trigger. This meets the ACS criteria, but could potentially leave a few airways unprotected from time to time. Only about 5% of centers use the higher GCS levels with the exception of GCS 13. That seems to be another popular one.

Which one is right for you? GCS 8 will always work because it is the minimum requirement. My own personal threshold trends higher. I would rather be called to an activation and apply my own judgement rather than come running only when the patient needs to be intubated followed by a trip to the OR for craniotomy.

You will need to work with your emergency physicians, trauma surgeons, and neurosurgeons to determine their collective comfort levels. It comes down to a balance between safety and unnecessary intubation. Look at your own center’s experience and pick a threshold that achieves a proper balance of overall patient safety.