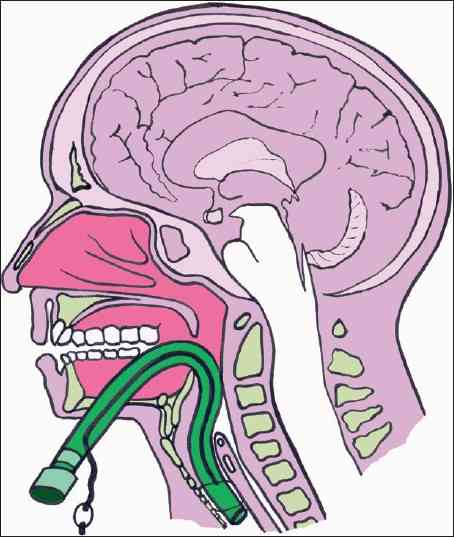

In my last post, I reviewed the classic, “old-timey” subxyphoid approach to the pericardial window procedure for trauma. Today, I’ll describe the operative approach if you are already in the abdomen managing injuries there.

The same considerations apply to these patients in deciding to perform the window. Either there is a suspicion of actual pericardial tamponade based on physiology or diagnostic imaging, or an injury has been noted in proximity to the heart that raises that suspicion.

If you are already exploring the abdomen, the procedure is much simpler. The instruments required are already in your laparotomy setup:

- Two toothed forceps

- Tissue (Metzenbaum) scissors

First, and most importantly, the upper abdomen must be evacuated of all blood. This is critically important since a positive window is solely determined by the presence of blood in the pericardial fluid. If it is contaminated with blood as it flows into the peritoneal cavity, a false positive may result leading to an unneeded thoracotomy or sternotomy.

The midline incision must extend to the xiphoid process in order to get adequate exposure of the diaphragm. The left lobe of the liver is retracted downwards by your assistant, and the two of you can then grasp an area of the pericardial portion of the diaphragm with the toothed forceps. As it is tented away from the heart, the scissors are used to dissect through both the diaphragm and pericardium. Although some use cautery for this, I’m a weenie using electricity near the heart.

The diaphragm is thick, so expect to cut through several mm of tissue before you see pericardial fluid. Watch the color of the fluid carefully. If it is the least bit blood tinged, the result is positive. And be sure to watch for 15-30 seconds. Sometimes the initial fluid is amber, but it becomes bloody as more is drained.

Bloody fluid equals positive result. This means that a thoracic procedure is indicated to evaluate the heart and repair the injury. The choice of sternotomy vs thoracotomy is determined by mechanism, foreign body trajectory, and suspected area of injury on the heart.

If the result is negative, you may close the hole with your suture of choice. If the abdomen is contaminated from a bowel injury, I recommend you use the traditional subxiphoid approach separate from the laparotomy incision to avoid contaminating the pericardial sac.

Here’s a YouTube video of a transdiaphragmatic window created laparoscopically. Since abdominal explorations for major trauma seldom lend themselves to laparoscopy, don’t get any ideas from watching this!