Happy Thanksgiving!

Enjoy these turkeys playing football (soccer for my US readers)

Happy Thanksgiving!

Enjoy these turkeys playing football (soccer for my US readers)

Last year, a lot of the papers presented at EAST were a bit ho-hum. But I’ve been reviewing the abstracts for the upcoming January 2016 meeting, and there’s a lot of good stuff! Although you do need to take this with a grain of salt, because sometimes the paper does not live up to the hype of the abstract. But many of the abstracts look so good, that I’m going to dedicate both December and January Trauma MedEd newsletters to reviewing them.

There are lots of intriguing ideas coming! Here are a few that I will be writing about:

Anyone on the subscriber list as of midnight (CST) Sunday night will receive it later that night Everybody else will have to wait for me to release it here on the blog late next week. So sign up for early delivery now by clicking here!

Focused abdominal sonography for trauma (FAST) has been around in one form or another for about 40 years. Sonographic examination of the abdomen was used in Europe in the 1970s, while the US was using diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL). FAST finally moved to the US in the 1990s and continues to this day. It has also been incorporated in the Advanced Trauma Life Support Course sponsored by the American College of Surgeons.

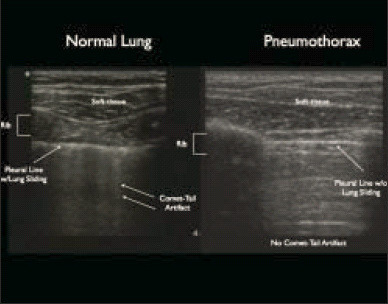

About 10 years ago, emergency physicians began using sonography to evaluate the thorax as well. The technique was primarily used to detect air (and possibly fluid) in the pleural space. Sensitivity and specificity have increased nicely over the years as the technology and our experience has improved.

Most trauma centers incorporate FAST into their trauma activations. Although it was initially vetted using blunt trauma patients, it can be and is used for evaluation in penetrating trauma. But relatively few centers expanded it to eFAST to evaluate the chest. Should they?

Bottom line: Definitely! Extended FAST adds about a minute to the overall exam and may provide information before the chest x-ray is obtained. It may also show pathology that the typical trauma chest x-ray cannot due to patient body habitus and supine positioning. I recommend that the eFAST be the standard of care in trauma activations if you have an ultrasound machine. Important! But be sure to have a way to record and perform quality reviews of the information obtained.

Related posts:

A lot of papers have been written on the use of thromboelastography in trauma. And pretty much any meeting or course you may attend has at least one talk on it. And I get it. It can be an important tool in treating trauma patients who have some sort of coagulation disturbance. It helps us figure out what specific part of the coagulation process is out of whack and suggests how we can fix it.

But there are a few problems, as I mentioned yesterday. And the “friction” that those issues cause overall decreases how useful it is. Here’s a partial list of the problems:

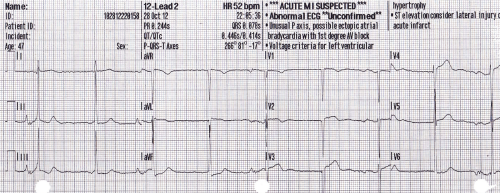

The main issue is that the current state of TEG and ROTEM are very similar to the state of electrocardiography shortly after it’s discovery. Here’s what you got then:

In order to get the most from an EKG, you need to combine this tracing with that from other leads, do a bunch of measurements, look for abnormal shapes and elevations/depressions, etc. This is exactly where we are with TEG and ROTEM today. Relatively crude, and it takes a lot of work to use it.

The tracing below shows where we are with EKGs today. A computer program looks at all the tracings, and rapidly applies a complex set of rules to come to a set of diagnoses. Notice in the image below that this reading is “unconfirmed.” But how many times in your career have you seen a cardiologist correct one of these? The machines are actually very good!

Bottom line: The tracing above is where we need to be with TEG and ROTEM. Instead of a clinician staring at a developing tracing and figuring out what products to give, these machines need to be just like an automated EKG machine. Sure, a human can still stare at the trace. But the machine will automatically monitor it, apply rules about what abnormalities are present and what is needed to correct them. Send off your blood specimen, and within minutes instructions like “infuse 2 units of plasma now” or “give 12u cryo now” appear. These may be displayed on a monitor in the treatment area, or be broadcast to the phone or pager of the responsible clinicians.

Current TEG/ROTEM equipment is what I would consider 1st generation. The next generation will reduce or remove much of the “friction” in the current process and allow us to really integrate TEG/ROTEM meaningfully into the massive transfusion protocol for trauma. And for anyone who develops this 2nd generation equipment, don’t forget my royalty checks for this idea!

Related post:

The new hot items in trauma care are thromboelastography (TEG) and ROTEM (thromboelastometry), a new spin on TEG from the TEM Corporation. These tools allow for in-depth assessment of factors that influence clotting. We know that rapidly recognizing and treating coagulopathy in major trauma patients can reduce mortality. So many trauma centers are clamoring to buy this technology, citing improved patient care as the reason.

But new technology is always expensive, and isn’t always all it’s cracked up to be. TEG and ROTEM require an expensive machine and a never-ending supply of disposable cartridges for use. Some hospitals are reluctant to provide the funds unless there is a compelling clinical need.

Surgeons at the University of Cincinnati compared the use of TEG with good, old-fashioned point-of-care (POC) INR testing in a series of major trauma patients seen at their Level I center.

Here are the factoids:

Bottom line: Point of care INR testing and TEG both correlate well with the need for blood products in major trauma patients. But POC INR is much cheaper and faster. Granted, the TEG gurus will say that you can tailor the products administered to meet the exact needs of the patient. But in all my travels, I have never visited a center that has fully and effectively incorporated TEG or ROTEM into their massive transfusion protocol. Before you make the financial leap to buy these new toys, make sure that you have a very good clinical reason to do so.

Related posts:

Reference: All the bang without the bucks: defining essential point-of-care testing for traumatic coagulopathy. J Trauma 79(1):117-124, 2015.