Several products for compressing the fractured pelvis are available. They range from free and simple (a sheet), to a bit more complicated and expensive. How to decide which product to use? Today, I’ll discuss the four commonly used products. Tomorrow, I’ll look at the science.

First, let’s dispense with the sheet. Yes, it’s very cheap. But it’s not easy to use correctly, and more difficult to secure. Click here to see my post on its use.

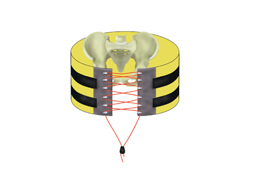

There are three commercial products that are commonly used. First is the Pelvic Binder from the company of the same name (www.pelvicbinder.com). It consists of a relatively wide belt with a tensioning mechanism that attaches to the belt using velcro. One size fits all, so you may have to cut down the belt for smaller patients. Proper tension is gauged by being able to insert two fingers under the binder.

Next is the SAM Pelvic Sling from SAM Medical Products (http://www.sammedical.com). This device is a bit fancier, is slimmer, and the inside is more padded. It uses a belt mechanism to tighten and secure the sling. This mechanism automatically limits the amount of force applied to avoid problems with excessive compression. It comes in three sizes, and the standard size fits 98% of the population, they say.

Finally, there is the T-POD from Pyng Medical (http://www.pyng.com/products/t-podresponder). This one looks similar to the Pelvic Binder in terms of width and tensioning. It is also a cut to fit, one size fits all device. It has a pull tab that uses a pulley system to apply tension. Again, two fingers must be inserted to gauge proper tension.

So those are the choices. Tomorrow, I’ll go over some of the data and pricing so you can make intelligent choices about selecting the right device for you.

Related posts: