Patients who have sustained a traumatic pneumothorax occasionally ask how soon they can fly in an airplane after they are discharged. What’s the right answer?

The basic problem has to do with Boyle’s Law (remember that from high school?). The volume of a gas varies inversely with the barometric pressure. So the lower the pressure, the larger a volume of gas becomes. Most of us hang out pretty close to sea level, so this is not an issue.

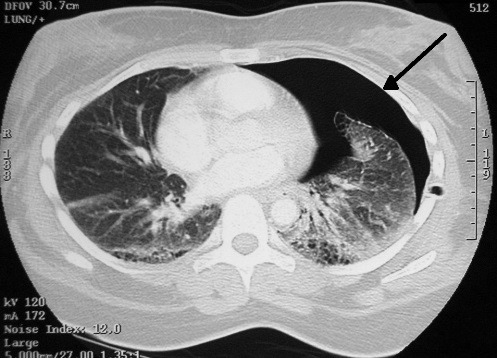

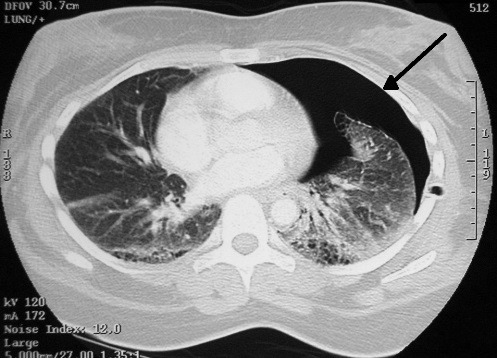

However, flying in a commercial airliner is different. Even though the aircraft may cruise at 30,000+ feet, the inside of the cabin remains considerably lower though not at sea level. Typically, the cabin altitude goes up to about 8,000 to 9,000 feet. Using Boyle’s law, any volume of gas (say, a pneumothorax in your chest), will increase by about a third on a commercial flight.

The physiologic effect of this increase depends upon the patient. If they are young and fit, they may never know anything is happening. But if they are elderly and/or have a limited pulmonary reserve, it may compromise enough lung function to make them symptomatic.

Commercial guidelines for travel after pneumothorax range from 2-6 weeks. The Aerospace Medical Association published guidelines that state that 2-3 weeks is acceptable. The Orlando Regional Medical Center reviewed the literature and devised a practice guideline that has a single Level 2 recommendation that commercial air travel is safe 2 weeks after resolution of the pneumothorax, and that a chest xray should be obtained immediately prior to travel to confirm resolution.

Bottom line: Patients can safely travel on commercial aircraft 2 weeks after resolution of pneumothorax. Ideally, a chest xray should be obtained shortly before travel to confirm that it is gone. Helicopter travel is okay at any time, since they typically fly at 1,500 feet or less.

References:

- Practice Guideline, Orlando Regional Medical Center. Air travel following traumatic pneumothorax. October 2009.

- Medical Guidelines for Airline Travel, 2nd edition. Aerospace Medical Association. Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine 74(5) Section II Supplement, May 2003.