Trauma is a surgical disease, and specifically, a disease of bleeding. So many of the tools and processes we have developed for its management revolves around the control of hemorrhage.

When a major trauma patient arrives in the resuscitation room, the initial management involves rapid assessment and correction of life-threatening conditions. Recognition of bleeding is paramount. A rapid decision must be made as to the source of hemorrhage and the best way to control it.

Traditionally, bleeding control has been relegated to the operating room. Body cavities are opened as appropriate, and exsanguination is controlled by clamping, repairing, and/or suturing.

However, some body regions are much more challenging. The most notable is the pelvis, and specifically, the unstable pelvis. In the old days, after wrapping or applying an external fixator, the best we could do was to ligate the internal iliac arteries bilaterally and hope the bleeding would slow down sufficiently (it never really stopped) so that internal packing might have a chance.

As the use of interventional radiography grew in trauma, it became possible to noninvasively occlude the internal iliacs. And then, the radiologists became skilled enough that they could selectively identify and embolize more distal bleeding vessels that would dramatically shut down pelvic bleeding.

But this introduced a conundrum. OR vs IR? Where to go after the trauma bay? I’ve long said that the only place an unstable trauma patient can go is to the OR. Not CT, and certainly not the radiology department.

Only the OR, because that’s the only place that something can actually be done about the bleeding. However, that’s not entirely true now.

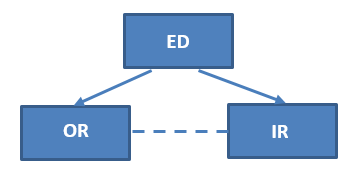

Here’s the traditional algorithm for a patient with hemorrhage from pelvic fractures:

They go to the operating room OR interventional radiology. If they start in the operating room and can be stabilized (think external fixation and/or preperitoneal packing), then they might be able to be packaged and taken to IR for embolization. And likewise, if they were initially stable enough to go to IR but crash there, then they must immediately be taken to OR.

But what if you could do both in one room?! That’s the beauty of the hybrid room! It is entirely possible to do two, three, and maybe more cases on the same patient in the same room. Hence, the hybrid OR.

Tomorrow, is the hybrid OR for trauma useful?