This 10 minute video was developed with prehospital providers in mind, but all trauma professionals will find some tidbits of interest.

Pay no attention to the hideous screenshot, though. I was not trying to look like House.

This 10 minute video was developed with prehospital providers in mind, but all trauma professionals will find some tidbits of interest.

Pay no attention to the hideous screenshot, though. I was not trying to look like House.

Social media usage is ubiquitous, and has a higher prevalence of usage in younger age groups. When the paper I am reviewing was written, 71% of adults with internet access reported using Facebook, and two thirds checked it daily. And now, three years later, I’m sure it’s used even more.

Unfortunately, many people don’t have a good sense of what is appropriate or not. And coupled with confusion about privacy settings, some post things that they probably shouldn’t. And unfortunately, everyone else on the internet can view them.

As a resident, it is more common to be “fired” from residency for unprofessional conduct, not cognitive failure or malpractice. When one is under investigation, the professional organization conducting it may look at prior behavior. And these days, that behavior may be years old and posted for all to see.

Is this a problem? Surgeons at the University of Nebraska were interested in how Facebook was used by surgical residents. They identified surgical residencies at 12 states in the Midwest region. They found all surgical residencies within the region and searched their program websites for the names of active residents. Facebook accounts were then created by the authors and were used to determine which of these residents had their own accounts.

The researchers then viewed those pages and classified the content into three categories: professional, potentially unprofessional, and clearly unprofessional. Definitions were based on criteria from the ACGME and the AMA. Accounts that were not accessible to the public were judged professional.

A total of 57 surgical residencies were identified, and 40 provided an institutional website with a current roster of their residents. Of 996 surgical residents, the accounts of 319 residents could be evaluated.

Here are the factoids:

Bottom line: Be careful! The use of social media is pervasive. Inappropriate or unprofessional can end a career, or can come back to haunt you years later. And this phenomenon is not limited to surgical residents. All professionals, even attending physicians, may succumb to its charms.

Know the social media policy for your hospital or residency program. Be very careful, and think very carefully about everything you post. Take advantage of built-in privacy settings for the platform you are using. But don’t assume that using them will keep inappropriate material from getting out. If in doubt, show your potential post to a trusted and reliable friend for a “second opinion.” Otherwise you may find your (not so) friendly “compliance police” knocking on your door. And possibly ending your career.

Reference: An assessment of unprofessional behavior among surgical residents on Facebook: a warning of the dangers of social media. J Surg Educ 71(6):e28-e32, 2014.

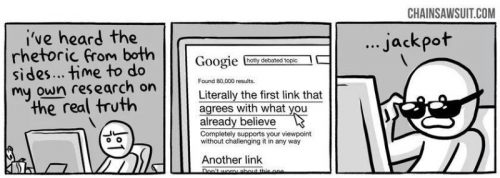

Source: http://chainsawsuit.com/comic/2014/09/16/on-research/

I sat in on a committee meeting once where the management of a particular clinical problem was being vigorously discussed. One of the participants pulled out his smartphone, did a quick search, and said, “Aha! This article shows that my opinion is correct!”

This approach is wrong on so many levels, it’s almost laughable. But it illustrates a real weakness that all human beings have: susceptibility to cognitive bias.

Scientists have identified somewhere between 150 and 200 different types of cognitive bias, and trying to sort them out will literally make your head spin. For a quick and enlightening read, I recommend reading the article below. It sifts through the mess and lumps them into four understandable categories.

Bottom line: We are all capable of warping what we read, hear, and see to fit our own vortex of pre-existing beliefs. It’s very important to recognize the possibility of bias when you are seeking information so that you can do everything to minimize its impact. If you can’t or won’t do that, then you’ll end up being that know-it-all guy with the smartphone.

Related post:

Trauma training during general surgery residency has changed dramatically over the past two decades. Although we like to blame the 80-hour work week rule on everything, there are other factors that may be at play. Increasing use of nonoperative management, availability and increasing scope of interventional radiologists, and the increasing number of surgical subspecialists are certainly significant.

The surgical group at LAC+USC looked at changes in operative caseloads, type of surgery performed, and the impact that concurrent subspecialty training has had on trauma operative volumes. The authors reviewed 16 years of ACGME data on resident surgical procedures in various body regions by year of training. They specifically looked at the impact of implementation of the 80-hour work week.

Here are the factoids:

Bottom line: Well, it was a catchy title, at least. Or is it a promotion for trauma fellowships? I hope the authors have some really good statistics to help this paper out. You may not be able to read the table above well, but the differences between pre-80 hour and post-80 hour are not that impressive, and the SD or SEM (can’t tell what they are) are uncommonly narrow, which amplifies the p values. And other than the number of laparotomies going up, the other numbers looked fairly constant. I look forward to the presentation and critique of this paper at the meeting. Not sure it will escape unscathed.

Reference: Is your graduating general surgery resident qualified to take trauma call? A 15-year appraisal of the changes in general surgery education for trauma. AAST 2016, Paper 39.

What exactly is pimping? If you have ever been a medical student or resident in any discipline, you probably already know. It’s ostensibly a form of Socratic teaching in which an attending physician poses a (more or less) poignant question to one or more learners. The learners are then queried (often in order of their status on the seniority “totem pole”) until someone finally gets the answer. But typically, it doesn’t stop there. Frequently, the questioning progresses to the point that only the attending knows the answer.

So how did this time honored tradition in medical education come about? The first reference in the literature attributes it to none other than William Harvey, who first described the circulatory system in detail. He was disappointed with his students’ apparent lack of interest in learning about his area of expertise. He was quoted as saying “they know nothing of Natural Philosophy, these pin-heads. Drunkards, sloths, their bellies filled with Mead and Ale. O that I might see them pimped!”

Other famous physicians participated in this as well. Robert Koch, the founder of modern bacteriology, actually recorded a series of “pümpfrage” or “pimp questions” that he used on rounds. And in 1916, a visitor at Johns Hopkins noted that he “rounded with Osler today. Riddles house officers with questions. Like a Gatling gun. Welch says students call it ‘pimping.’ Delightful.”

So it’s been around a long time. And yes, it has some problems. It promotes hierarchy, because the attending almost always starts questions at the bottom of the food chain. So the trainees come to know their standing in the eyes of the attending. And they also can appreciate where their fund of (useful?) knowledge compares to their “peers.” It demands quick thinking, and can certainly create stress. And a survey published last year showed that 50% of respondents were publicly embarrassed during their clinical rotations. What portion of this might have been due to pimping was not clear.

Does pimping work? Only a few small studies have been done. Most medical students have been involved with and embarrassed by it. But they also responded that they appreciated it as a way to learn. A 2011 study compared pimping (Socratic) methods to slide presentations in radiology education. Interestingly, 93% preferred pimping, stating that they felt their knowledge base improved more when they were actively questioned, regardless of whether they knew the answer.

So here are a few guidelines that will help make this technique a positive experience for all:

For the “pimpers”:

For the “pimpees”:

Bottom line: Pimping is a time-honored tradition in medicine, but should not be considered a rite of passage. There is a real difference in attitudes and learning if carried out properly. Even attendings have a thing or two to learn about this!

Reference: The art of pimping. JAMA. 262(1):89-90, 1989.