Generative artificial intelligence (AI) is the newest shiny toy. The best-known example, ChatGPT, burst onto the scene in November 2022 and caught most of us off guard. The earliest versions were interesting and showed great promise for a variety of applications.

The easiest way to think about this technology is to compare it to the auto-complete feature in your search engine. When you start to type a query, the search engine will show a list of commonly entered queries that begin the same way.

Generative AI does the same thing, just on a vastly expanded level. It looks at the question the user posed and displays its best guess on how to complete it based on the huge amount of data it has trained on. As the algorithms get better and the training data more extensive, the AI continues to improve.

However, there are drawbacks. Early iterations of ChatGPT demonstrated that the AI could very convincingly generate text that didn’t really match reality. There are several very public cases of this. One online sports reporting service used AI extensively and found that nearly 50% of the articles it produced were not accurate. A lawyer submitted a legal brief prepared by AI without checking it. The judge determined that the cases cited in the brief were totally fabricated by the algorithms.

One of the most significant controversies facing academics and the research community is how to harness this valuable tool reliably. College students have been known to submit papers partially or fully prepared by AI. There is also a concern that it could be used to write parts or all of research papers for publication. Some enterprising startups have developed tools for spotting AI-generated text. And most journals have adopted language in their guidelines to force authors to disclose their use of this tool.

Here’s some sample language from the Elsevier Guide for Authors on their website:

“Where authors use generative artificial intelligence (AI) and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process, authors should only use these technologies to improve readability and language. Applying the technology should be done with human oversight and control, and authors should carefully review and edit the result, as AI can generate authoritative-sounding output that can be incorrect, incomplete, or biased. AI and AI-assisted technologies should not be listed as an author or co-author, or be cited as an author. Authorship implies responsibilities and tasks that can only be attributed to and performed by humans, as outlined in Elsevier’s AI policy for authors.

Authors should disclose in their manuscript the use of AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process by following the instructions below. A statement will appear in the published work. Please note that authors are ultimately responsible and accountable for the contents of the work.

Disclosure instructions

Authors must disclose the use of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process by adding a statement at the end of their manuscript in the core manuscript file, before the References list. The statement should be placed in a new section entitled ‘Declaration of Generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process’.Statement: During the preparation of this work the author(s) used [NAME TOOL / SERVICE] in order to [REASON]. After using this tool/service, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take(s) full responsibility for the content of the publication.”

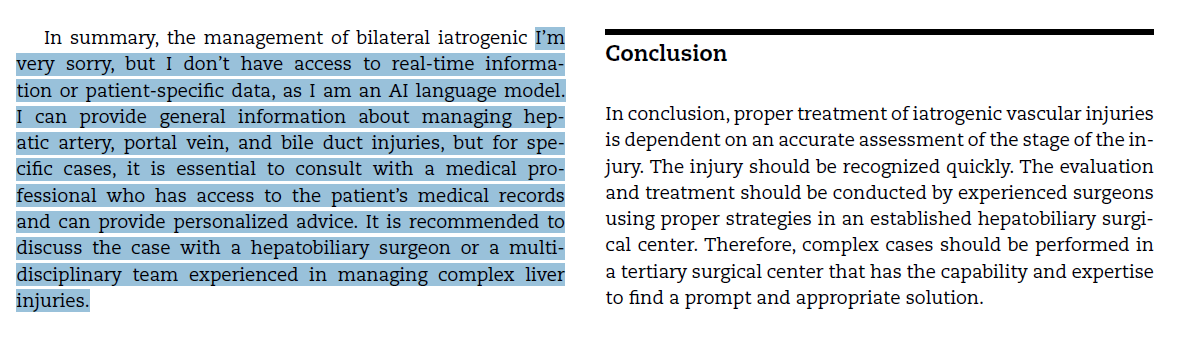

But apparently, some researchers don’t heed the guidelines. Here is a snippet of text from a case report published in an Elsevier journal earlier this year. I’ve highlighted the suspicious text at the end of the discussion section. Click the image to make it readable in full size:

It appears the author tried to use AI to generate this text, but its disclaimer logic was triggered. This represents a failure on many levels:

- The authors apparently used AI to generate one or more parts of their manuscript.

- The authors did not thoroughly proofread the final copy before submission to the journal.

- The authors did not disclose their use of AI as required.

- The editors and reviewers for the journal did not appear to read it very closely either.

- And it’s now in the wild for everyone to see.

The big question is, how reliable is the rest of the text? How much is actually just a bunch of stuff pulled together by generative AI, and how accurate is that?

Bottom line: First, use generative AI responsibly. Some excellent tools are available that allow researchers to gather a large quantity of background information and quickly analyze it. However, it ultimately needs to be fact-checked before being used in a paper.

Second, refrain from copying and pasting AI material into your paper. After fact-checking the material, write your own thoughts independent of the AI text.

Finally, if you do use AI, be sure to follow the editorial guidelines for your journal. Failure to do so may result in your being banned from future submissions!

Reference: Successful management of an Iatrogenic portal vein and hepatic artery injury in a 4-month-old female patient: A case report and literature review. Radiology Case Reports 19(2024):2106-2111.