There are three organ systems that are classically involved in FES: pulmonary, CNS, and skin. Manifestations generally begin between 24 and 72 hours after injury. In rare cases, symptoms can begin within 12 hours. In my experience, these tend to be the ones that become the most severe and are frequently life-threatening.

Pulmonary (95% of cases): This is the most common manifestation of FES, and may occur without other signs and symptoms. Nearly all patients develop some degree of hypoxia. Progressive tachypnea and mild tachycardia may provide the first clinical clue if oxygen saturation is not being monitored.

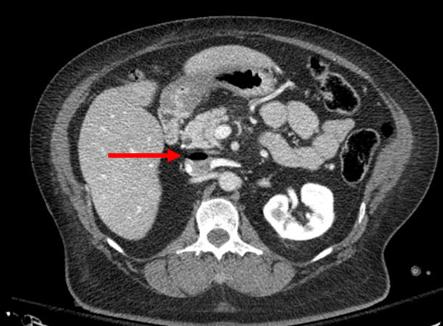

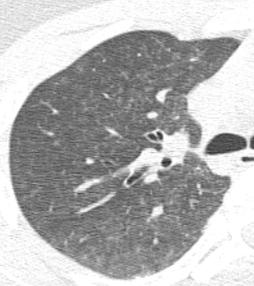

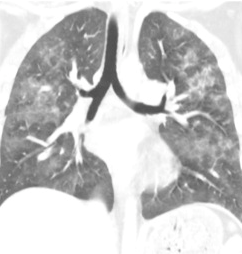

Chest x-ray is usually unremarkable early on. And once the syndrome has developed, it is generally not helpful. CT scan is useful for defining the extent of pulmonary injury, but lags the clinical picture by several days. Findings are non-specific, usually consisting of small, ground-glass opacities in the periphery.

In the example above, the opacities are very small and difficult to see.

But they’re a little more obvious here!

Other CT findings include small pulmonary nodules in the upper lobes or along peripheral pulmonary vessels. These are thought to be areas of obstruction caused by the emboli. Nonspecific pleural effusions may be seen, and bronchial thickening has also been described. Rarely, fat globules may be seen in the lower extremity veins or IVC, and should immediately raise suspicion for developing FES even before symptoms develop.

CNS (60% of cases): If they occur, CNS changes generally crop up after the pulmonary manifestations begin. Generally, they start as mild confusion, but can progress to decreasing level of consciousness and even coma. Focal neurologic deficits are occasionally seen, and seizures can occur.

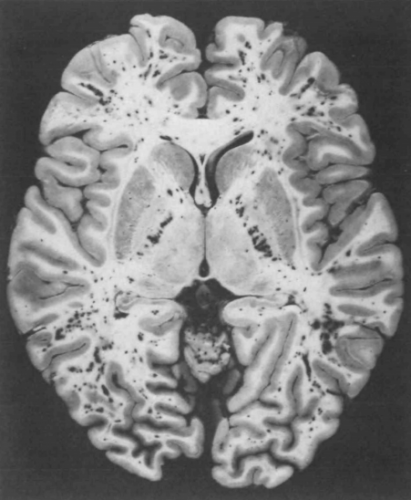

The actual mechanism behind this appears to be very similar to the skin changes which will be described in the next section. Emboli occur in vessels predominantly in the white matter of the brain. This leads to petechial hemorrhages, which are likely due to the inflammatory mechanisms previously described.

Note the numerous dark petechiae visible in the white matter in this specimen.

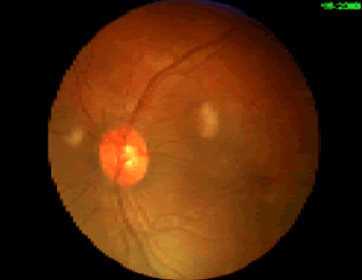

Retinal exam can also show evidence of fat embolism. Fat globules may actually be seen in the retinal vessels early.

Note the fat globules at the 9:30 and 2:00 positions to the optic nerve in the image above.

Skin (33% of cases): The most recognizable sign of FES is the petechial skin rash. This rash usually involves the torso, and axillary petechiae are very common. It can spread to involve the head and neck, and occasionally the extremities. Subconjunctival hemorrhages are sometimes seen. The rash tends to be transient and usually lasts only a few days. Here is an example of the classic petechial rash.

Other findings: Fat globules may be found in the urine in patients with FES. However, they are commonly present in patients with long bone fractures, so their presence is not helpful or predictive. Nonspecific findings such as fever, leukocytosis, anemia, and thrombocytosis are also relatively common. In severe cases, cardiac dysfunction, hypotension, and peripheral hypoperfusion can occur. I have personally seen necrosis of fingers and toes from a very severe case.

Unfortunately, the “classic” triad of mental status changes, skin rash, and pulmonary insufficiency are seen in only a small minority of patients. Typically, only one or two signs and symptoms appear at the same time, making diagnosis a bit challenging.

Tomorrow, making the diagnosis of fat embolism syndrome.