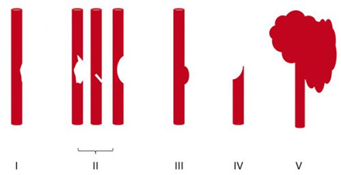

In my last post, I reviewed the grading system for blunt carotid and vertebral artery injury (BCVI). Today, we’ll discuss treatment, and in the next post, we will wrap up with pediatric-specific information.

There are basically three modalities at our disposal for managing BCVI: antithrombotic medication (heparin and/or antiplatelet agents), surgery, and endovascular procedures. The choice of therapy is usually based on surgical accessibility and patient safety for anticoagulation. We know that several studies have shown decreased stroke events in heparinized patients. Unfortunately, this is not always possible due to associated injuries. Antiplatelet agents are usually tolerated after acute trauma, especially low-dose aspirin. However, several studies have shown little difference in outcomes in patients receiving heparin vs. aspirin/clopidogrel for BCVI.

So what to do? Here are some broad guidelines:

- Grade I (intimal flap). Heparin or antiplatelet agents should be given. If heparin can be safely administered, it may be preferable in patients needing other surgical procedures since it can be rapidly reversed by stopping the infusion. These lesions generally heal entirely on their own, so a follow-up CT angiogram should be scheduled in 1-2 weeks. Medication can be stopped when the lesion heals.

- Grade II (flap/dissection/hematoma). These injuries are more likely to progress, so heparin is preferred if it can be safely given. Stenting should be considered, especially if the lesion progresses. Long-term anti-platelet medication may be required.

- Grade III (pseudoaneurysm). Initial heparin therapy is preferred unless contraindicated. Stable pseudoaneurysms should be followed with CTA every six months. If the lesion enlarges, surgical repair should be performed in accessible injuries or stenting in inaccessible ones.

- Grade IV (occlusion). Heparin therapy should be initiated unless contraindicated. Patients who do not suffer a catastrophic stroke may do well with follow-up antithrombotic therapy. Endovascular treatment does not appear to be helpful.

- Grade V (transection with extravasation). This lesion is frequently fatal, and the bleeding must be addressed using the best available technique. For lesions that are surgically accessible, the patient should undergo the appropriate vascular procedure. Inaccessible injuries should undergo angiographic treatment and may require embolization to control bleeding without regard for the possibility of stroke.

References:

- Scott WW, Sharp S, Figueroa SA, et al. Clinical and radiographic outcomes following traumatic Grade 1 and 2 carotid artery injuries: a 10-year retrospective analysis from a Level I trauma center. J Neurosurg 122:1196, 2015.

- Scott WW, Sharp S, Figueroa SA, et al. Clinical and radiographic outcomes following traumatic Grade 3 and 4 carotid artery injuries: a 10-year retrospective analysis from a Level 1 trauma center. J Neurosurg 122:610, 2015.

- Scott WW, Sharp S, Figueroa SA, et al. Clinical and radiological outcomes following traumatic Grade 1 and 2 vertebral artery injuries: a 10-year retrospective analysis from a Level 1 trauma center. J Neurosurg 121:450, 2015.

- Scott WW, Sharp S, Figueroa SA, et al. Clinical and radiological outcomes following traumatic Grade 3 and 4 vertebral artery injuries: a 10-year retrospective analysis from a Level I trauma center. The Parkland Carotid and Vertebral Artery Injury Survey. J Neurosurg 122:1202, 2015.