I’ll spend the next two posts discussing plasma. This is an important component of any trauma center’s massive transfusion protocol (MTP). Coagulopathy is the enemy of any seriously injured patient, and this product is used to attempt to fix that problem.

And now there are two flavors available: liquid plasma and fresh frozen plasma. But there is often confusion when discussing these products, especially when there are really three flavors! Let’s review what they are exactly, how they are similar, and how they differ.

Fresh frozen plasma (FFP)

This is plasma that is separated from donated whole blood. It is generally frozen within 8 hours, and is called FFP. However, in some cases it may not be frozen for a few more hours (not to exceed 24 hours total) and in that case, is called FP24 or FP. It is functionally identical to FFP. But note that the first “F” is missing. Since it has gone beyond the 8 hour mark, it is no longer considered “fresh.” To be useful in your MTP, it must be thawed, and this takes 20-40 minutes, depending on technique.

Thawed plasma

Take a frozen unit of FFP or FP, thaw, and keep it in the refrigerator. Readily available, right? However, the clock begins ticking until this unit expires after 5 days. Many hospital blood banks keep this product available for the massive transfusion protocol, especially if other hospital services are busy enough to use it if it is getting close to expiration. Waste is bad, and expensive!

Liquid plasma (never frozen)

This is prepared by taking the plasma that was separated from the donated blood and putting it in the refrigerator, not the freezer. It’s shelf life is that of the unit of whole blood it was taken from (21 days), plus another 5, for a total of 26 days. This product used to be a rarity, but is becoming more common because of its longer shelf life compared to thawed plasma.

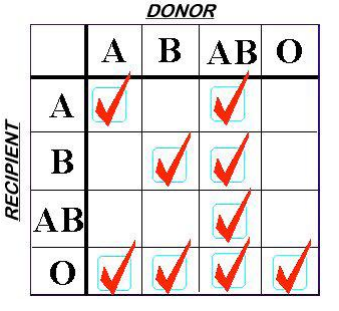

Finally, a word on plasma compatibility. ABO compatibility is still a concern, but Rh is not. There are no red cells in the plasma to carry any of the antigens. However, plasma is loaded with A and/or B antibodies based on the donor’s blood type. So the compatibility chart is reversed compared to what you are accustomed to when giving red cells.

Remember, you are delivering antibodies with plasma and not antigens. So a Type A donor will have only Type B antibodies floating around in their plasma. This makes it incompatible with people with blood types B or AB.

Type O red cells are the universal donor type because the cells have no antigens on the surface. Since Type AB donors have both antigens on their red cells, they have no antibodies in their plasma. This makes AB plasma is the universal donor type. Weird, huh? Here’s a compatibility chart for plasma.

Next time, I’ll discuss the virtues of the various types of plasma when used for massive transfusion in trauma.