It is almost a given that low-grade solid organ injuries are relatively benign and seldom require any intervention. In fact, some trauma centers actually discharge these patients home from the emergency department.

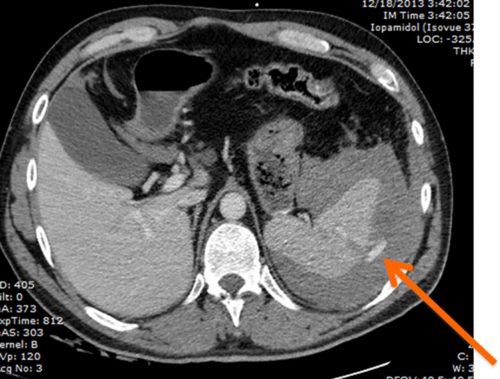

But what about low-grade isolated spleen injuries with a contrast blush? Apparently, a few authors believe that this may be a benign condition that doesn’t require any specific management. This didn’t sit well with some, and a multicenter study was launched to look at this group more closely.

A retrospective cohort study involving 21 trauma centers was organized via the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma. It enrolled adults (>18 years) with a grade I or II injury on CT scan after blunt trauma, which also demonstrated a contrast blush. Hemodynamically unstable patients and those who had clotting disorders or were taking any anticoagulant other than aspirin were excluded.

Here are the factoids:

- Although 209 patients were enrolled over a nearly six-year period, 64 were removed due to meeting exclusion criteria or undergoing some intervention or laparotomy for other injuries

- The remaining 145 patients were 66% men with an average age of 47

- About one-third had a grade I injury, and two-thirds had grade II

- 20% of these patients failed nonoperative management

- These results were unchanged between grade I (18%) and grade II (21%)

- Those who failed had a longer hospital stay (8 days vs. 5 days), had a higher likelihood of blood transfusion (55% vs. 26%) and MTP activation (14% vs. 3%)

- There was no difference in discharge disposition or mortality

Bottom line: This study was conducted between 2014 and 2019. During that period, the AAST spleen and liver injury grading scales did not consider vascular injury. The 2018 update automatically upgrades injuries with blush or extravasation to Grade IV. This has a significant impact on how we view these injuries.

I have always said that any patient with contrast extravasation is bleeding to death until we stop it. The only exception is pediatric patients, who seem to clot these on their own. The 2018 update bore this out, and this paper confirms that low-grade anatomic injuries become dangerous if extravasation is present. I would also extend this to patients with a CT showing significant pseudoaneurysm formation.

So what should you do? If you have a patient with a spleen or liver injury that has contrast extravasation or a pseudoaneurysm, consider this a patient that needs hemorrhage control by interventional radiology under Standard 4.15 in the 2022 ACS Resources for Optimal Care of the Injured Patient. This means that you must let your IR team know that you have a patient who needs an intervention within 60 minutes, or you will need to transfer to a center with those capabilities as soon as possible.

Reference: Failure rates of nonoperative management of low-grade splenic injuries with active extravasation: an Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma multicenter study. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open. 2024 Mar 7;9(1):e001159. doi: 10.1136/tsaco-2023-001159. PMID: 38464553; PMCID: PMC10921525.