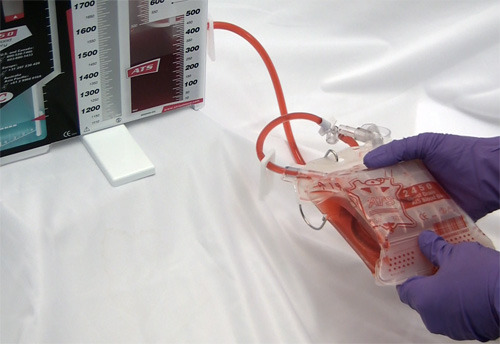

Autotransfusing blood that has been shed from the chest tube is an easy way to resuscitate trauma patients with significant hemorrhage from the chest. Plus, it’s usually not contaminated from bowel injury and it doesn’t need any fancy equipment to prepare it for infusion.

It looks like fresh whole blood in the collection system. But is it? A prospective study of 22 patients was carried out to answer this question. A blood sample from the collection system of trauma patients with more than 50 cc of blood loss in 4 hours was analyzed for hematology, electrolyte and coagulation profiles.

The authors found that:

- The hemoglobin and hematocrit from the chest tube were lower than venous blood (Hgb by about 2 grams, Hct by 7.5%)

- Platelet count was very low in chest tube blood

- Potassium was higher (4.9 mmol/L), but not dangerously so

- INR, PTT, TT, Factor V and fibrinogen were unmeasurable

Bottom line: Although shed blood from the chest looks like whole blood, it’s missing key coagulation factors and will not clot. Reinfusing it will boost oxygen carrying capacity, but it won’t help with clotting. You may use it as part of your massive transfusion protocol, but don’t forget to give plasma and platelets according to protocol. This also explains why you don’t need to add an anticoagulant to the autotransfusion unit prior to collecting or giving the shed blood!

Related post: Chest tubes and autotransfusion

Reference: Autotransfusion of hemothorax blood in trauma patients: is it the same as fresh whole blood? Am J Surg 202(6):817-822, 2011.