I’ve written about the use of lytics to treat retained hemothorax over the past few days. Although it sounds like a good idea, we just don’t know that it works very well. And they certainly don’t work fast. Lengths of stay were on the order of two weeks in both studies reviewed.

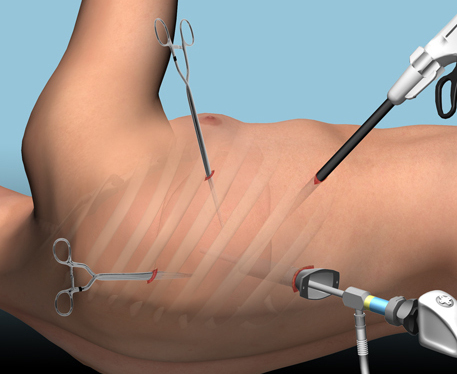

The alternative is video assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS). So let’s take a look at what we know about it. This procedure is basically laparoscopy of the chest. A camera is inserted, and other ports are added to allow insertion of instruments to suck, peel, and scrape out the hemothorax.

A prospective, multi-center study was performed over a 2 year period starting in 2009. Twenty centers participated, contributing data on 328 patients with retained hemothorax. This was defined as CT confirmation of retained blood and clot after chest tube placement, with evidence of pleural thickening.

Here are the factoids:

- 41% of patients had antibiotics given for chest tube placement (this is interesting given the lack of consensus regarding their effectiveness!)

- A third of patients were initially managed with observation, and most of them (82%) did not need any further procedures (83 of 101 patients)

- Observation was more successful in patients who were older, had smaller hemothoraces (<300cc), smaller chest tubes (!!, <34 Fr), blunt trauma, and peri-procedure antibiotics (?)

- An additional chest tube was inserted in 19% of patients, image guided drain placement in 5%, and lytics in 5%. Half to two-thirds of these patients required additional management.

- VATS was used in 34% of patients. One third of them required additional management including another chest tube, another VATS, or even thoracotomy.

- Thoracotomy was most likely required if there was a diaphragm injury or large hemothorax (<900cc)

- Empyema and pneumonia were common (27% and 20%, respectively)

Bottom line: There’s a lot of data in this paper. Most notably, many patients resolve their hemothorax without any additional management. But if they don’t, additional tubes, guided drain placement, and lytics work only a third of the time and contribute to additional time in the hospital. Even VATS and thoracotomy require additional maneuvers 20-30% of the time. And infectious complications are common. This is a tough problem!

Tomorrow, I’ll try to roll it all together and suggest an algorithm to try to optimize both outcomes and cost.

Posts in this series:

Reference: Management of post-traumatic retained hemothorax: A prospective, observational, multicenter AAST study. 72(1):11-24, 2012.