Earlier this week, I wrote about a new tool for monitoring over- and under-triage for trauma programs. In place of using ISS as the metric for triggering review, the Need For Trauma Intervention (NFTI) is based on resource utilization during the initial portion of the hospital stay.

The original study was performed at a single Level I trauma center in Dallas. The authors then rolled it out as a multicenter study to test its overall reliability. However, the authors changed the focus in this work. The original paper focused on the development of a new tool to improve upon the evaluation of proper decisions to activate the trauma team. The authors have now extrapolated that their system predicts when a patient’s physiologic reserve is depleted. In turn, this should be the indicator that a trauma activation is needed.

The authors performed a convenience sample of 38 trauma centers around the US. Of these, 25 were adult only, 3, pediatric only, and 10 were combined adult/peds centers. Two years of data were collected from each. Injury severity score (ISS) and revised trauma score (RTS) were calculated for all patients. Outcomes analyzed were discharge location (home vs ongoing care), complications, and length of stay.

A complicated statistical model was adopted that evaluated the associations between higher ISS (> 15), lower RTS (< 7.84) and any positive NFTI factor. To refresh your memory, here’s the list of NFTI factors:

- blood transfusion within 4 hours of arrival

- discharge from ED to OR within 90 minutes of arrival

- discharge from ED to interventional radiology (IR)

- discharge from ED to ICU AND ICU length of stay at least 3 days

- require mechanical ventilation during the first 3 days, excluding anesthesia

- death within 60 hours of arrival

Here are the factoids regarding the new study:

- Nearly 90,000 patient encounters were submitted over a 2 year period

- The risk of experiencing a complication increased by 9x if NFTI+, 6x for ISS>15, and 5x for RTS<7.84

- Odds of discharge to a continuing care facility was about 2.5x more likely if any of the three thresholds were met

- Length of stay was significantly better predicted by NFTI

The authors conclude that NFTI was a better indicator of major trauma when compared to ISS and RTS. They claim that it is the best single definition because the model fit is better and that it has stronger associations with complications, discharge location, and length of stay.

Bottom line: Hmm, I’m not so sure. It’s a great idea and does allow us to drill down on those patients most in need of high-level trauma center resources. The authors admit that each tool (ISS, RTS, and NFTI) identifies some important patients that the others do not. It just seems that more of them tend to be identified by NFTI.

I always worry when complicated statistical models are needed to show these differences. This is a complex concept, so more sophisticated models may indeed be needed by virtue of the data that needs to be analyzed. Overtriage can be easily identified in many cases when NFTI- patients trigger a full trauma activation. Obvious undertriage occurs in NFTI+ patients with no activation.

But NFTI still does not obviate the need to search harder for undertriage. What about the case of a stab to the chest in the “box” region, who does not end up with a cardiac injury or hemo/pneumothorax? They would be NFTI- but mechanism positive.

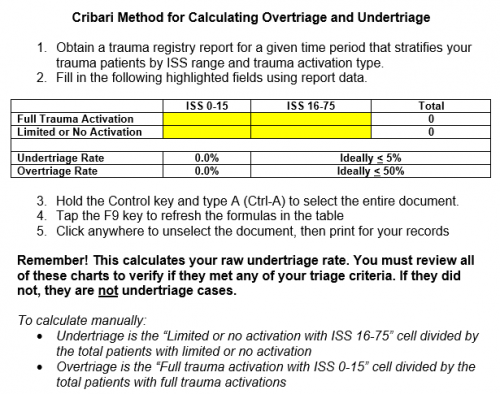

How do we learn from NFTI+ patients who did not have a trauma activation. Just like using the Cribari grid, we must look at each individual chart and ask two questions:

- Did this patient meet any of our highest level activation criteria? If so, it is frank undertriage.

- If not, do we need a new criterion to catch this in the future?

So NFTI is a somewhat improved version of the Cribari grid. Sure, it can predict complications better, as well as length of stay (which may be related). But not discharge location, as claimed. As for being an indicator of depleted patient reserve, I think that’s just speculation at this point. Both tools can be used to automatically generate data for review from the trauma registry. And both will have some false negatives and positives.

My recommendation: This paper provides an academic argument that NFTI is somewhat better than the Cribari method. Now it’s time to get practical. Some enterprising trauma centers need to do a study where they use both systems side by side. How many charts for review are generated by each? How many false negatives and positives are there? How much work (abstractor / registrar time) is needed to analyze and act on the results? This is the only way we can answer the question of which one is better in the real world.

Reference: Rethinking the definition of major trauma: The Need For Trauma Intervention outperforms Injury Severity Score and Revised Trauma Score in 38 adult and pediatric trauma centers. J Trauma publish ahead of print, 2019.