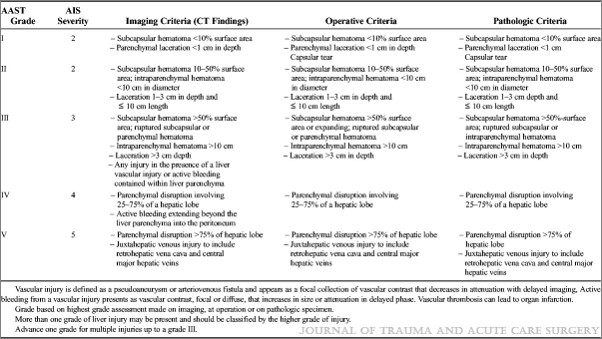

In my last post, I reviewed the updated AAST organ injury scaling (OIS) for the spleen. Today, I’ll share details of the new version of liver grading.

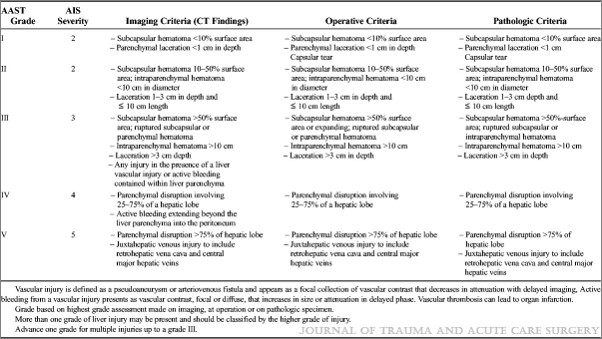

First, the overall focus of the updated liver scale is similar to the spleen one: it incorporates a listing of criteria identified by CT scan that parallels the old anatomic criteria. The CT column contains all the old anatomic stuff, but now includes scaling for active bleeding.

The confusing part? Whereas contained active bleeding within the spleen was Grade IV and active bleeding escaping the spleen was Grade V in the updated scale, these drop down a grade in the liver. So bleeding contained with the liver parenchyma is Grade III and active extravasation escaping into the peritoneal cavity is only Grade IV. I presume this has to do with the abbreviated injury score (AIS) used to calculate ISS, and that the mortality hit from this degree of bleeding is less than that of the spleen.

The final difference between the updated scale and the original is the removal of Grade VI. This was previously described as hepatic avulsion, which is a nonsurvivable injury. The AIS for Grade VI liver used to be 6, which causes an immediate ISS calculation short circuit to 75. Which also means that survival is approximately 0%. This is not part of the OIS update, which may be due to the fact that it never occurs in anyone who makes it to a trauma center alive.

Here are the updated guidelines. Click the image or link below it to open a bigger image in a new window.

Click to download larger image

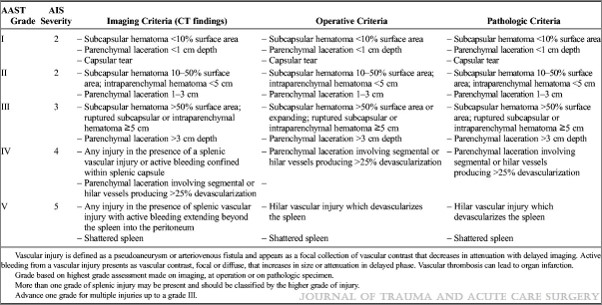

Click to download larger image

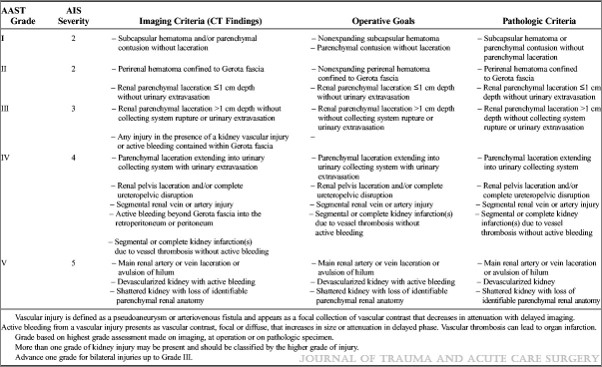

In the next post, I’ll review the new features of the kidney injury scale.